In the arts and crafts of Egypt may be found the reflection of her age-long history. Egypt, the cradle of civilisation, is also the cradle of the arts and the home of craftsmanship. The race that wrought the glorious monuments of Pharaonic and Islamic architecture is no less remarkable in the skill it brings to bear on the minor domestic and, as it were, secular arts. In one sense it may be said that Egyptian arts and crafts, far more

than architecture, sculpture and painting, convey the sense of continuity

in the Egyptian race. For, as Sir Denison Ross points out in "The Art of

Egypt through the Ages", "it must be realised that art in Egypt was so

inextricably bound up with religion that, when the old religion was supplanted

by a new one, the old art likewise disappeared the old Pharaonic art disappears

entirely from the valley of the Nile with the

The earliest examples of craftsmanship which have come down to us are

those of the Predynastic period (more than 3000 years B.C.). As might be

expected the ravages of time have destroyed almost every object of a perishable

nature such as for instance wood and leather. But beautiful examples of

the potters' and vase-makers' work have been preserved. The potter's wheel

was unknown in those distant days yet many of the vases are perfectly rounded

and the ageless beauty of

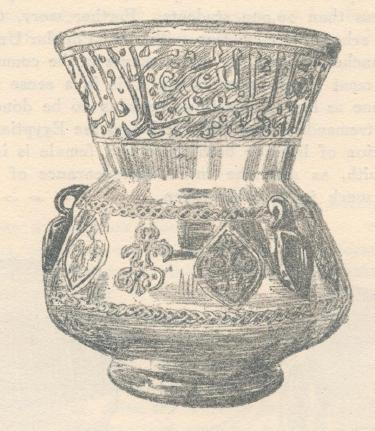

Jewellery also has come down to us from those distant days. From the First Dynasty there is, in the Cairo Museum, a set of four bracelets found in the tomb of Zer at Abydos. It is the earliest known example of Egyptian jewellery but for centuries before that the Egyptians had been making beads and ornaments of amethyst, lapis lazuli, cornelian and other semi-precious Stones. By the Twelfth Dynasty the jeweller's skill had attained something as near perfection as is possible in an imperfect world. Casting, chasing and engraving of precious metals were commonplaces of his daily work and cloisonne work was already well known. For technical skill, delicacy of handling and for the love of nature which the design reveals there can be few more beautiful achievements than the two coronets of Khnemit, now in the Cairo Museum. Garlands of flowers such as that in one of these two lovely coronets are also found in necklaces of the Eighteenth Dynasty. They were copied from floral garlands used at festivals and included most of the flowers and fruits grown in Egyptian gardens such as cornflowers, daisies, lotuses, dates and pomegranates. More ornate, more flamboyant is the jewellery of Tutankhamen's time. Its treasures, also to be seen in the Cairo Museum, include gold filigree and granulated gold-work, and the visitor hardly knows what, amid such splendours, to admire most. The gold mask of the adolescent king, the headdress and collar inlaid with coloured glass, is an item which few travellers forget. But just as fascinating are the smaller specimens of the ancient jewellers' art : the pectoral ornaments inlaid with semi precious stones, the earrings in which birds of blue glass stand out on a background of cloisonne. Anyone of the aspects of Egypt ian craftsmanship throughout the ages would require, to do it justice, a volume or several volumes to itself and there exists a very considerable literature on this and kindred subjects. Take for instance the subject of glazes and glass. Of these the ancient Egyptians were the original inventors and the series of examples that have come down to us is itself a fascinating piece of history. Here we can only mention a few examples: the beautiful faience tiles discovered in the palace of Rameses III at Medinet Habu (in Cairo Museum), the lovely chalice in blue-glazed faience (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), the wishing cups of the Tutankhamen period, the turquoise-blue glass head rest with a gold collar round its stem.  Spinning and weaving are ancient Egyptian crafts. The earliest known examples of tapestry-weaving are some fragments found at the beginning of the present century in the tombs of Amenhotep II and Thutmosis IV. Originally white the linen cloth is woven in blue, red, green, yellow, brown and black. Througbout the centuries Egyptian tapestry weaving and embroidery was of the highest standard and, when the empire and religion of the Pharaohs had vanished, the Christian Egyptians not only carried on the textile art but brougbt it to a higher degree of perfection than it had ever before reached. The Graeco-Roman period may be described as a transition epoch. The coming of Islam was to modify and transform not only religion and thought but most of the outward manifestations of Egyptian civilisation. The craftsman's skill however, remained. In textiles for instance the weaving works at Fostat attained a virtual supremacy; linen was woven into such delicate fabric that a whole length of turban linen could be threaded through a finger ring. Embroidery and tapestry flourished and, later, after the Turkish invasion, gold and silver thread work and velvet embossed with precious metal became part of the Egyptian textile-worker's handicraft. The joiners and carpenters developed, under Islam, a characteristic form of craftsmanship known as Mashrabiya. This wooden lattice work, originally designed to serve as a window screen from the sun's rays, played a large part in domestic architecture and in the manufacture of railings, furniture and, sometimes, in the construction of prayer-niches in mosques. An art in great honour in mediaeval Egypt, as indeed it is in Egypt today, was that of calligraphy. Arabic script is highly decorative and the ingenuity and taste of the Egyptian craftsman applied it to such diverse materials as stone, plaster, wood, metal, ceramic, glass and textiles. Inscriptions from the Koran were frequently used and no time, trouble or expense was deemed too great for the reproduction of the word of God.  As a corollary to calligraphy bookbinding also attained a high level of excellence in Islamic Egypt. Intricate tooling, elaborate leather work were lavished on the bindings of the Koran. Leather-work for other purposes was also in honour. Many beautiful examples of saddles, bags and mats, may still be seen as they left the hands of the mediaeval worker. But by far the greater part of what remains is, naturally enough by reason of its durability, the metal work of the mediaeval ages. The most intricate work in copper and brass offered no terrors to the Egyptian workman who prided himself on "working metal as though it were thread ". That consummate skill was dis played in stands for the Koran, in trays, in boxes, in locks and in decorative work on gates and doors. To this day there are craftsmen in Cairo who can reproduce the masterpieces of their forefathers and when, a few years ago, it was desired to make a presentation to a distin~ished foreign savant, a Cairo workman was found who, with no machinery and ,vith no help save that of his son, was able to make an exact replica of a table in wrought brass which, in the Cairo Museum, excites the wondering admiration of all beholders. When original and replica were placed side by side it was defficult to tell one from the other. Egypt's traditions of craftsmanship in ceramics and glassware were also retained when, politically and historically, Ancient Egypt was no more. There are a number of minor arts, still flourishing today, which link mediaeval Egypt with Egypt of the twentieth century. Matting, made from woven palm fibre, is one of them and, without seeing, it is difficult to realise how pleasing to the eye this somewhat unpromising material may be made. Carpet-weaving has, of late years, enjoyed a literal renaissance, and, at the Paris Exhibition of 1937, Egyptian carpets attracted the admiring attention of all who saw them. Silk-weaving too is also enjoying a new lease of life. The tradition

of heavy, hard-wearing silk, has always been maintained at Damietta and

elsewhere in the Egyptian Delta. But designs had become stereotyped and

formal. Within the past few years modern design has added its charms to

the consummate quality and durability of Egyptian silks and the results

can and do hold an honoured place among beautiful fabrics of the modern

world. Fashions wax and wane; taste

|