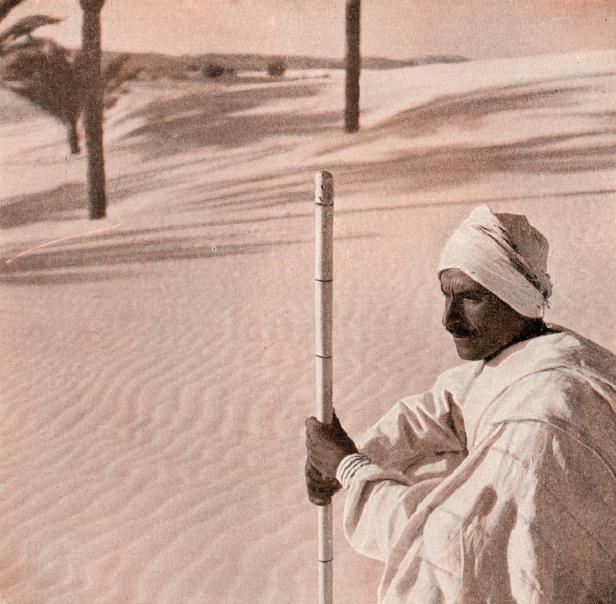

0n either side of the Nile Valley the desert plateau extends from the

southern borders of Egypt to the Delta in the North. Between the Nile and

the Red Sea the width of the wilderness varies from 90 to 350 miles and

is known in the north as the Arabian Desert. On the west the Desert of

Libya has no natural barrier for hundreds of miles; it is indeed a part

of the immense Sahara Desert, to many minds, is synonymous with monotony,

flatness and aridity. This is only a half-truth, for the scenery of the

desert offers, to the observant eye, as much variety as a fertile landscape.

In the North of Egypt the desert is certainly flat but from Cairo southwards

it rises to 1000 and even 1500 feet above sea level in a series of terraces

or small plateaus rising one above the other and intersected by small ravines

worn by the occasional rainstorms which burst in their neighbourhood. These

plateaus, with occasional hills, cut up by valleys (wadis) and sometimes

by deep ravines constitute the principal type of scenery of the Egyptian

Deserts.In the Arabian Desert it ends on the Eastern Side in a chain of

mountains running parallel to the Red Sea and the Gulf of Suez.

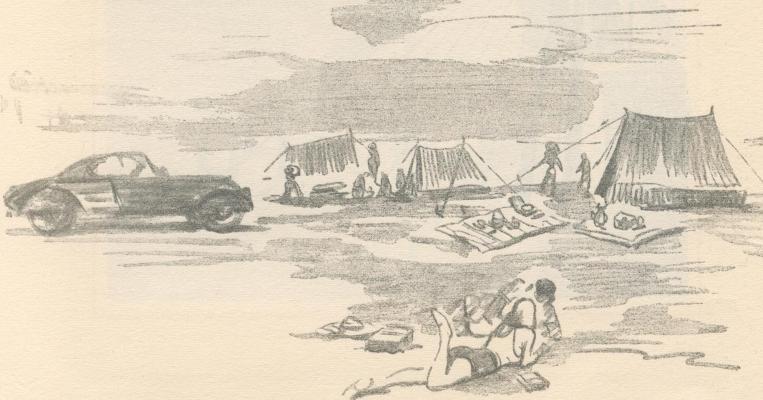

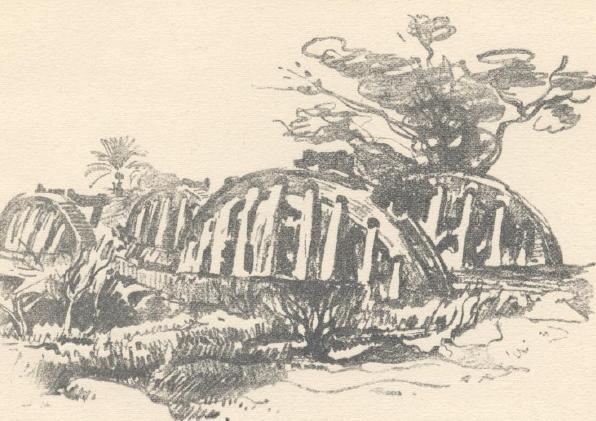

Siwa, a large oasis in the Libyan Desert is also known as the oasis of Ammon or Jupiter Ammon. Its ancient Egyptian name was Sekhet-am, or "Palm Land" Six miles long by four to five miles wide, the oasis lies about 350 miles west of Cairo. Herodotus describes the oracle temple of Ammon which enjoyed world fame and was consulted by Alexander the Great. The remains of this temple are at a little distance from the town of Siwa. It is a small building with inscriptions dating from the 4th century B.C. Hallowed for centuries, the oracle fell into gradual disrepute and was reported dumb in A.D. 160. Siwa, from a holy city, became a place of banishment for criminals and political offenders. After the Arab invasion of Egypt Siwa became independent and remained so for centuries until it was occupied by Mohammed Aly in 1820. It is now governed by its own sheikhs under the control and supervision of the Egyptian Government.  The name of the oasis appears in hieroglyphics as Kenem and that of its capital as Hebi (the plough). It is usually identified with the city of Oasis mentioned by Herodotus as being seven days journey from Thebes and called in Greek the Island of the Blessed. In Pharaonic times it supported a large population but the numerous ruins are nearly all of later date. As in Siwa there is at Kharga the ruin of a temple of Ammon but perhaps the most interesting ruin is the necropolis or burial-place of the early Christians. It consists of about two hundred rectangular tomb buildings in most of which there is also a mummy chamber, for the Egyptian christians at first continued this method of preserving the bodies of their dead.  All these oases are practically rainless. Their water is derived from numerous wells springing from the porous sandstone which underlies a great portion of the Libyan Desert. Some very ancient wells are 400 feet deep. Date palms are the principal crop of most oases and their fruit is considered superior to that grown in the Nile Valley. Rice, barley and wheat are also cultivated at Kharga where the dom palm, the tamarisk, the acacia and the wild senna are also found. Industries are few though the baskets and mats woven in the oases from palm leaves and fibre find a ready sale. Latterly the carpet industry or rather the home-craft of carpet weaving has been started in several of these desert "islands". Remote from the amenities of civilisation, restricted in their opportunities for social intercourse, it might be supposed that emigration to the valley. would take a large toll of the population of the oases. This however is not the case. Many of the young men leave their distant homes to go and work in Egypt proper; but their one ambition is to return home as soon as they have amassed a small sum of money. Town life and modern amenities have little or no charm for these sons of the desert to whom their distant fastness is ever the most beautiful spot on earth. The attraction of desert solitudes is not confined to those who are born therein. For centuries the desert has been the refuge of anchorites and monks who desire to flee the noise and bustle of the world. Monasteries in the desert are very numerous, perhaps the most famous being that of Saint Catherine in the Sinai Peninsula. It was from this ancient monastery that Tischendorf, a German savant, "borrowed" a manuscript which he never returned and which has since become famous as the "Codex Sinaiticus". Tischendorf presented the manuscript to the Czar of Russia and its sale by the Soviet Government to the British Museum was one of the sensations of the year 1933. Motoring in the desert is a comparative novelty. It was at one time a somewhat hazardous undertaking but the Royal Automobile Club of Egypt has now issued detailed itineraries of all available routes. Given a car in good condition and an adequate supply of petrol, oil and water, there is nothing to fear in venturing out into the desert and the absence of traffic and noise gives to driving a keen edge of pleasure that is never experienced when driving in towns or even rural districts. Desert camping is the almost inevitable corollary of desert motoring.

Life under canvas in the pure clear air of the desert has always had a

particular fascination for visitors to Egypt and a stay of any length in

the country almost invariably included a few days camping out under the

stars. The last few years however have witnessed an extraordinary extension

of the camping holiday. Many townsfolk indeed have made of week-end camping

a regular feature of their lives and, a site having been chosen, the tent

is left as a permanent fixture from one season to another.

There is camping deluxe and camping. Some prefer to take with them the equipment which will ensure a supply of hot water, a wellsprung mattress, several course meals and a well-laid table. Others enjoy the fun of improvised meals and makeshift contrivances. A third category prefers to take no luggage at all and to put up at one or other of the little Rest Houses which are to be found on many of the desert routes. These things are of course a matter of taste. But one experience is

common to all Campers in the desert: it is the waking up in the morning

,vith what a former Governor of Sinai has described as that "All's right

,vith the world feeling", when one recaptures "the enthusiasms, raptures

and morning appetite of one's long-past and much regretted teens".

|