7/5/2010

|

During my trip to China in

June 2010, I participated in a “future of computing”

conference in Changsha, and had a chance to look around

the environment of the capital of Hunan Province. |

Changsha

is a little village of about six million people that most Americans

have never heard of. It does not make even the list of top 25

Chinese cities in population, though if it were in the US, it would

be fourth behind New York, Los Angeles and Chicago. Changsha

is the capital of Hunan Province, so the food is quite spicy and

tasty.

Changsha

is a little village of about six million people that most Americans

have never heard of. It does not make even the list of top 25

Chinese cities in population, though if it were in the US, it would

be fourth behind New York, Los Angeles and Chicago. Changsha

is the capital of Hunan Province, so the food is quite spicy and

tasty. As we approached the city, we saw

the same style of high-rise construction that I had noted in

Beijing, though here it was spread out to a number of areas of the

city, not continuous throughout. We soon arrived at a fancy

hotel complex called the Venice Hotel that fancies itself to be

Italy transplanted to China. The pictures at the right will give you

some idea of the effect. The hotel is on an island surrounded

by a canal both of whose ends meet a tributary of the Xiang River,

which itself flows north into the Yangzi (Yangtze). The hotel has a

nautical theme, in concert with its name, and a large fake boat

makes for a lovely outdoor playground for children and parties

alike. I also enjoyed their huge outdoor swimming pool and

smaller indoor pool. It is not near the center of Changsha,

but large apartment buildings under construction were visible in

several directions, and the lobby contained a mockup of the island,

appearing to offer real estate for sale in future houses. As

we approached, solar panels surmounted every roof. Food was

(too) plentiful, including a “noodle bar” where you could get your

favorite type of noodles, with various mix-ins, in a cup of chicken

broth.

As we approached the city, we saw

the same style of high-rise construction that I had noted in

Beijing, though here it was spread out to a number of areas of the

city, not continuous throughout. We soon arrived at a fancy

hotel complex called the Venice Hotel that fancies itself to be

Italy transplanted to China. The pictures at the right will give you

some idea of the effect. The hotel is on an island surrounded

by a canal both of whose ends meet a tributary of the Xiang River,

which itself flows north into the Yangzi (Yangtze). The hotel has a

nautical theme, in concert with its name, and a large fake boat

makes for a lovely outdoor playground for children and parties

alike. I also enjoyed their huge outdoor swimming pool and

smaller indoor pool. It is not near the center of Changsha,

but large apartment buildings under construction were visible in

several directions, and the lobby contained a mockup of the island,

appearing to offer real estate for sale in future houses. As

we approached, solar panels surmounted every roof. Food was

(too) plentiful, including a “noodle bar” where you could get your

favorite type of noodles, with various mix-ins, in a cup of chicken

broth. The conference was at the same

hotel, and for the honored guests and organizers, began with a

private banquet on the evening we arrived. This was held in an

upstairs suite in the hotel, where the only thing that surprised me

was that two flat-screen TV’s were blasting as we arrived, one in

the suite’s reception room, and one in the dining room.

Fortunately, they fell silent quickly, but I wonder if this might be

customary. As we went around the table introducing ourselves

to each other, our host stopped me after I had introduced myself as

a professor at MIT, to point out that I was in fact an

“academician”, being a member of the US National Academy’s Institute

of Medicine, and that this was a really big deal in China. One

of the Chinese scholars at the table was a member of the Chinese

Academy of Science, and he was treated with great deference both at

dinner and at the subsequent conference. So in fact I leaned

something new. When I had read of Soviet-era “Academician”

somebody in the USSR, I assumed this was just a way to say

“academic”, or professor; it must have meant a member of the

academy. I like spicy food, so I was quite happy with the Hunan

palette. The most novel thing I ate was what looked like a giant sea

snail, with a helical shell. The creature within had been

extracted, cooked (I don’t know in which order), sliced into thin

slices, and spiced, and then returned to the shell. It had the

texture of squid or abalone, a bit chewy. I’m not sure I would

fly 24 hours to sample it again, but it was good.

The conference was at the same

hotel, and for the honored guests and organizers, began with a

private banquet on the evening we arrived. This was held in an

upstairs suite in the hotel, where the only thing that surprised me

was that two flat-screen TV’s were blasting as we arrived, one in

the suite’s reception room, and one in the dining room.

Fortunately, they fell silent quickly, but I wonder if this might be

customary. As we went around the table introducing ourselves

to each other, our host stopped me after I had introduced myself as

a professor at MIT, to point out that I was in fact an

“academician”, being a member of the US National Academy’s Institute

of Medicine, and that this was a really big deal in China. One

of the Chinese scholars at the table was a member of the Chinese

Academy of Science, and he was treated with great deference both at

dinner and at the subsequent conference. So in fact I leaned

something new. When I had read of Soviet-era “Academician”

somebody in the USSR, I assumed this was just a way to say

“academic”, or professor; it must have meant a member of the

academy. I like spicy food, so I was quite happy with the Hunan

palette. The most novel thing I ate was what looked like a giant sea

snail, with a helical shell. The creature within had been

extracted, cooked (I don’t know in which order), sliced into thin

slices, and spiced, and then returned to the shell. It had the

texture of squid or abalone, a bit chewy. I’m not sure I would

fly 24 hours to sample it again, but it was good. Not all the talks were

in English, however, as some of the opening greetings and most of

the first two talks were by Chinese presenters, in Chinese.

Fortunately, a very helpful student named Chengkun Wu, from the

National University of Defense Technology, was assigned to translate

for me, and he did a great job of giving me a sense of what was

being said and of helping to orient me around Changsha during my

stay. Chengkun is going to Manchester this fall to pursue his

graduate studies, and must be one of the top students at his

university. I enjoyed his company, and Keith Marzullo and I

met with him and a number of his colleagues the following evening to

talk about how we think someone becomes a successful

researcher. My main emphasis was to learn that once you have

proven your ability to do really well in coursework and

examinations, those do not count any further. You need to play

with problems, understand what works and doesn’t in others’

solutions, and invent new ways to do things, even though they may

not work. I suspect this is not a lesson that has been

diligently taught in a country with a Confucian tradition where exam

taking is still most valued.

Not all the talks were

in English, however, as some of the opening greetings and most of

the first two talks were by Chinese presenters, in Chinese.

Fortunately, a very helpful student named Chengkun Wu, from the

National University of Defense Technology, was assigned to translate

for me, and he did a great job of giving me a sense of what was

being said and of helping to orient me around Changsha during my

stay. Chengkun is going to Manchester this fall to pursue his

graduate studies, and must be one of the top students at his

university. I enjoyed his company, and Keith Marzullo and I

met with him and a number of his colleagues the following evening to

talk about how we think someone becomes a successful

researcher. My main emphasis was to learn that once you have

proven your ability to do really well in coursework and

examinations, those do not count any further. You need to play

with problems, understand what works and doesn’t in others’

solutions, and invent new ways to do things, even though they may

not work. I suspect this is not a lesson that has been

diligently taught in a country with a Confucian tradition where exam

taking is still most valued. At

the conference banquet on Thursday night, I was astonished when one

of the Chinese organizers (at the right in the picture) sat in with

the traditional orchestra to play the Erhu, a two-stringed

violin-like instrument, but without a finger board. His

playing was amazing. When he started, I had my back turned, talking

with a colleague, and I at first thought I was hearing the

expressive nuances of a human voice singing a plaintive song.

He told me that he has been playing since childhood, and left me

with a much increased appreciation for this instrument. I had

only heard it before being played very badly by an elderly man in

Harvard Square.

At

the conference banquet on Thursday night, I was astonished when one

of the Chinese organizers (at the right in the picture) sat in with

the traditional orchestra to play the Erhu, a two-stringed

violin-like instrument, but without a finger board. His

playing was amazing. When he started, I had my back turned, talking

with a colleague, and I at first thought I was hearing the

expressive nuances of a human voice singing a plaintive song.

He told me that he has been playing since childhood, and left me

with a much increased appreciation for this instrument. I had

only heard it before being played very badly by an elderly man in

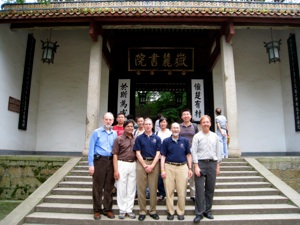

Harvard Square. The

following day, which was all presented in Chinese, we were whisked

off to visit the supercomputer center at the National University of

Defense Technology (NUDT), went through the Han Tombs exhibit at the

Hunan Provincial Museum, an exhibition of ancient artifacts from a

BC-era tomb, then had lunch at a restaurant run by Mao’s relatives,

and finally toured the Yuelu Academy, said to be the oldest

continually operating university in the world, dating to 976 AD.

The

following day, which was all presented in Chinese, we were whisked

off to visit the supercomputer center at the National University of

Defense Technology (NUDT), went through the Han Tombs exhibit at the

Hunan Provincial Museum, an exhibition of ancient artifacts from a

BC-era tomb, then had lunch at a restaurant run by Mao’s relatives,

and finally toured the Yuelu Academy, said to be the oldest

continually operating university in the world, dating to 976 AD. The visit started by having to put

plastic bag booties on our shoes, which was an impossible challenge

for my number 12 sized shoes. We then looked at a very typical

large computer room full of racks of electronics, which meant little

to me. I had recently been at the San Diego Supercomputer

Center, which to outward appearances seems very similar. Our

hosts were proud of having built not only the interconnect systems

of their machine but, in some versions, even their own domestic

processor. There was an exhibit of backplane and interconnect

technologies, and in one corner of the clean room we could see

people soldering new (or repair) boards. I wonder if burning

flux is good in a clean room. I can understand the practical

benefits of a strong supercomputer program, especially in designing

military technologies, but this did get a lot more concerted

attention than I am accustomed to in most US universities.

The visit started by having to put

plastic bag booties on our shoes, which was an impossible challenge

for my number 12 sized shoes. We then looked at a very typical

large computer room full of racks of electronics, which meant little

to me. I had recently been at the San Diego Supercomputer

Center, which to outward appearances seems very similar. Our

hosts were proud of having built not only the interconnect systems

of their machine but, in some versions, even their own domestic

processor. There was an exhibit of backplane and interconnect

technologies, and in one corner of the clean room we could see

people soldering new (or repair) boards. I wonder if burning

flux is good in a clean room. I can understand the practical

benefits of a strong supercomputer program, especially in designing

military technologies, but this did get a lot more concerted

attention than I am accustomed to in most US universities. The

tomb of Xin Zui, the Marquess of Dai, who died about 160 BC, along

with the tombs of her husband, the Marquis, and their son, form a

spectacular treasure from the time of the Han dynasty. They showcase

beautiful pottery, weapons, an exercise tutorial, Egyptian-like

shabti figures carved in wood to accompany the dead into the

afterlife as servants, spices, woven baskets, coins and jade disks,

musical instruments, cosmetics jars and cases, table bowls,

spectacular embroidered silks, bamboo tablets with tiny but precise

writing, and a series of caskets. The pièce de résistance is the

mummified body of the Marquess herself, preserved in anoxic water

when her tomb flooded soon after her burial. Needless to say,

I found the artifacts much more pleasing than the mummy!

The

tomb of Xin Zui, the Marquess of Dai, who died about 160 BC, along

with the tombs of her husband, the Marquis, and their son, form a

spectacular treasure from the time of the Han dynasty. They showcase

beautiful pottery, weapons, an exercise tutorial, Egyptian-like

shabti figures carved in wood to accompany the dead into the

afterlife as servants, spices, woven baskets, coins and jade disks,

musical instruments, cosmetics jars and cases, table bowls,

spectacular embroidered silks, bamboo tablets with tiny but precise

writing, and a series of caskets. The pièce de résistance is the

mummified body of the Marquess herself, preserved in anoxic water

when her tomb flooded soon after her burial. Needless to say,

I found the artifacts much more pleasing than the mummy!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ch'ang-sha

1925

Ch'ang-sha

1925