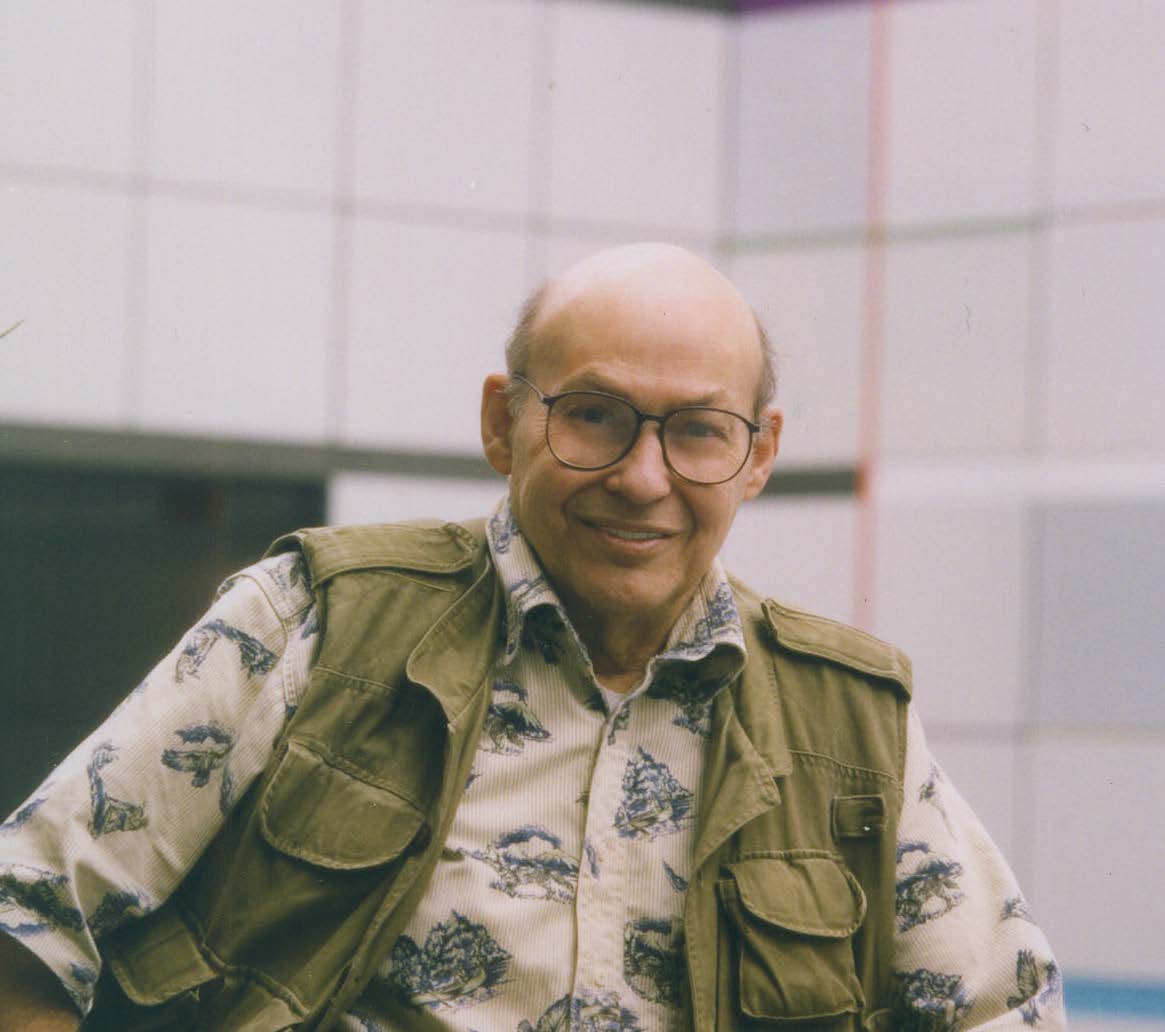

Marvin Minsky

|

Marvin Minsky passed away on January 24, 2016.

Many years ago, when I was a student casting about for what I wanted to do, I wandered into one of Marvin's classes. Magic happened. I was awed and inspired. I left that class saying to myself, “I want to do what he does.”

I have been awed and inspired ever since. Marvin became my teacher, mentor, colleague, and friend. I will miss him at a level beyond description.

Marvin was a highly creative visionary who believed that computers would someday think like we think and surpass us.

He always knew what to do next. He developed programs of research, he started laboratories, he taught inspiring subjects, he attracted and mentored pioneering students, he developed new concepts and invented new words to label them.

Marvin's impact was enormous. People came to MIT's Artificial Intelligence Laboratory from everywhere to benefit from his wisdom and to enjoy his deep insights, lightning-fast analyses, and clever jokes. They all understood they were witnessing an exciting scientific revolution. They all wanted to be part of it.

In Marvin's laboratory, we all worked on a time-shared computer with a few megabyes of magnetic memory cores. It was the biggest memory in the world. Wonderful things happened on that computer, but your cell phone today has 50,000 times more power.

Of course, there was no internet, and no remote access. If you wanted to use the computer, you had to be there, so if you happened to live in the other Cambridge, you migrated to this Cambridge. If you happened to live in this Cambridge, you spent most of your time in the AI Laboratory. The laboratory had as many people at 3am as at 3pm.

For a long time, I was afraid to disagree with Marvin, thinking if I saw something in a different light, it must be the wrong light. Then, it occurred to me that if we switched sides on a subject, he could still crush me, so it was ok to disagree.

Marvin had a short attention span. Whenever I tried to explain an idea to him, he would guess what it was after a few sentences. Often his guess was a better idea. Once I explained that if we ever developed really intelligent machines, we should do a lot of simulation before we turned them loose in our world to be sure they weren't dangerous. “Oh,” he said, “and we are the simulation?” guessing the end of my not-yet-complete joke. “The simulation is not going very well, is it,” he continued.

Marvin had great patience with students but no patience with those who doubted that computers would ever be intelligent at a human level or beyond. In the early days, there were plenty of doubters, so there was a lot of public arguing. He would often dismiss the doubters as victims of the “unthinkability fallacy.” That happens when someone identifies something a computer can't do, and then offers an argument that boils down to “I can't think of how a computer could do x, therefore a computer cannot do x.”

Marvin thought it ironic that the doubters of the possibility have turned into worriers about the consequences. He didn't see a technical advance that would justify the change, attributing recent successes to faster computers.

Marvin was a total egalitarian. He didn't care what you looked like, what your gender was, or how old you were. He only cared about your ideas and abilities. He asked my colleague, Professor Gerald Sussman, to run the Laboratory's important “summer vision project” when Gerry was still an undergraduate. He asked me to take over as Director of the AI Laboratory when I was a newly hired Assistant Professor, infuriating the MIT administration. He didn't care. He told me I would only have to be director for a year or two. It turned out to be a quarter century.

Marvin's books are extremely clear and well organized, but his lectures were not. They were inspirational rather than tutorial; they were opportunities to see a great thinker think out loud. Every lecture or two, he would say something you would think about for a year. One day a student asked him about approaches to learning that involve the adjustment of numerical weights. He said, “The trouble with weights is that they can't talk about themselves.” I still think about that.

Marvin believed in multiplicities. Our thinking, he wrote, rests on many ways of doing things, many levels of reasoning, many kinds of description, many meanings of words, and many cooperating little agents. He said, “If you only have one way to think about something, you have no hope if you get stuck.”

Marvin liked to talk about “suitcase words,” such as intelligence, creativity, and emotion. He pointed out that all these words are like big suitcases into which you can stuff anything. Intelligence cannot be defined because it is a collection of capabilities, not just one. He once said that, sure, Watson (the Jeopardy program) is intelligent, but not intelligent in the ways we are.

In the early days, Marvin wasn't much interested in human intelligence, arguing that intelligence doesn't depend, as Ed Fredkin likes to say, on whether the machine is wet or dry inside.

Nevertheless, Marvin and his colleague, Seymour Papert, were interested in developmental psychology. Marvin liked the story about his daughter, Juliana, then called Julie, who hung around the laboratory with her twin brother Henry and her older sister Margaret. Someone was doing the classic Piaget egg-cup experiment, using Julie as a subject. You show a child egg cups, each holding an egg. You let the child watch as you take the eggs out of the cups and spread them out. “Are there more eggs or egg cups,” he asked, wondering if Julie would say “more eggs,” the standard early childhood answer. All were delighted when Julie actually said, “You will have to ask Henry. I don't have conservation yet.”

Later on, Marvin focused on human thinking and especially on Freud's ideas. I particularly like his thoughts on “K-lines,” short for knowledge lines. It is a theory that much of human thinking involves putting yourself back into the same mental state you were in the last time you thought about a similar problem or situation.

Among Marvin's contributions are seminal books, The Society of Mind and The Emotion Machine. These books are like diamond mines. Many of the gems in those mines remain uncut, so you have to work on them a while before you see their brilliance. That is why they will be informing us for decades to come.

Marvin received important recognition from all over the planet. His awards include the ACM Turing award, the Japan Prize, the Benjamin Franklin Medal, and MIT's Killian Award.

In 2014, he received the Dan David Prize and the BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award.

My nomination letter for the BBVA award explains some of Marvin's contributions in more detail.

See also the following for more about his extraordinary life:

Celebrating Marvin Minsky's life at the Media Laboratory

26 January 2016