Type Theory

Univalent Foundations of Mathematics

The Univalent Foundations Program

Institute for Advanced Study

Homotopy Type Theory

Univalent Foundations of Mathematics

The Univalent Foundations Program

Institute for Advanced Study

“Homotopy Type Theory: Univalent Foundations of Mathematics”

© 2013 The Univalent Foundations Program

Book version: first-edition-652-g5c9d883

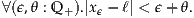

MSC 2010 classification: 03-02, 55-02, 03B15

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/.

This book is freely available at http://homotopytypetheory.org/book/.

Acknowledgment

Apart from the generous support from the Institute for Advanced Study, some contributors to the book were partially or fully supported by the following agencies and grants:

This material is based in part upon work supported by the AFOSR under the above awards. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the AFOSR.

This material is based in part upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under the above awards. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

A Special Year on Univalent Foundations of Mathematics was held in 2012-13 at the Institute for Advanced Study, School of Mathematics, organized by Steve Awodey, Thierry Coquand, and Vladimir Voevodsky. The following people were the official participants.

|

There were also the following students, whose participation was no less valuable.

|

In addition, there were the following short- and long-term visitors, including student visitors, whose contributions to the Special Year were also essential.

|

We did not set out to write a book. The present work has its origins in our collective attempts to develop a new style of “informal type theory” that can be read and understood by a human being, as a complement to a formal proof that can be checked by a machine. Univalent foundations is closely tied to the idea of a foundation of mathematics that can be implemented in a computer proof assistant. Although such a formalization is not part of this book, much of the material presented here was actually done first in the fully formalized setting inside a proof assistant, and only later “unformalized” to arrive at the presentation you find before you — a remarkable inversion of the usual state of affairs in formalized mathematics.

Each of the above-named individuals contributed something to the Special Year — and so to this book — in the form of ideas, words, or deeds. The spirit of collaboration that prevailed throughout the year was truly extraordinary.

Special thanks are due to the Institute for Advanced Study, without which this book would obviously never have come to be. It proved to be an ideal setting for the creation of this new branch of mathematics: stimulating, congenial, and supportive. May some trace of this unique atmosphere linger in the pages of this book, and in the future development of this new field of study.

The Univalent Foundations Program

Institute for Advanced Study

Princeton, April 2013

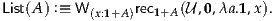

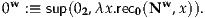

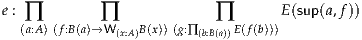

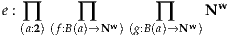

et is a ΠW-pretopos

et is a ΠW-pretopos

Homotopy type theory is a new branch of mathematics that combines aspects of several different fields in a surprising way. It is based on a recently discovered connection between homotopy theory and type theory. Homotopy theory is an outgrowth of algebraic topology and homological algebra, with relationships to higher category theory; while type theory is a branch of mathematical logic and theoretical computer science. Although the connections between the two are currently the focus of intense investigation, it is increasingly clear that they are just the beginning of a subject that will take more time and more hard work to fully understand. It touches on topics as seemingly distant as the homotopy groups of spheres, the algorithms for type checking, and the definition of weak ∞-groupoids.

Homotopy type theory also brings new ideas into the very foundation of mathematics. On the one hand, there is Voevodsky’s subtle and beautiful univalence axiom. The univalence axiom implies, in particular, that isomorphic structures can be identified, a principle that mathematicians have been happily using on workdays, despite its incompatibility with the “official” doctrines of conventional foundations. On the other hand, we have higher inductive types, which provide direct, logical descriptions of some of the basic spaces and constructions of homotopy theory: spheres, cylinders, truncations, localizations, etc. Both ideas are impossible to capture directly in classical set-theoretic foundations, but when combined in homotopy type theory, they permit an entirely new kind of “logic of homotopy types”.

This suggests a new conception of foundations of mathematics, with intrinsic homotopical content, an “invariant” conception of the objects of mathematics — and convenient machine implementations, which can serve as a practical aid to the working mathematician. This is the Univalent Foundations program. The present book is intended as a first systematic exposition of the basics of univalent foundations, and a collection of examples of this new style of reasoning — but without requiring the reader to know or learn any formal logic, or to use any computer proof assistant.

We emphasize that homotopy type theory is a young field, and univalent foundations is very much a work in progress. This book should be regarded as a “snapshot” of the state of the field at the time it was written, rather than a polished exposition of an established edifice. As we will discuss briefly later, there are many aspects of homotopy type theory that are not yet fully understood — but as of this writing, its broad outlines seem clear enough. The ultimate theory will probably not look exactly like the one described in this book, but it will surely be at least as capable and powerful; we therefore believe that univalent foundations will eventually become a viable alternative to set theory as the “implicit foundation” for the unformalized mathematics done by most mathematicians.

Type theory was originally invented by Bertrand Russell [Rus08], as a device for blocking the paradoxes in the logical foundations of mathematics that were under investigation at the time. It was later developed as a rigorous formal system in its own right (under the name “λ-calculus”) by Alonzo Church [Chu33, Chu40, Chu41]. Although it is not generally regarded as the foundation for classical mathematics, set theory being more customary, type theory still has numerous applications, especially in computer science and the theory of programming languages [Pie02]. Per Martin-Löf [ML98, ML75, ML82, ML84], among others, developed a “predicative” modification of Church’s type system, which is now usually called dependent, constructive, intuitionistic, or simply Martin-Löf type theory. This is the basis of the system that we consider here; it was originally intended as a rigorous framework for the formalization of constructive mathematics. In what follows, we will often use “type theory” to refer specifically to this system and similar ones, although type theory as a subject is much broader (see [Som10, KLN04] for the history of type theory).

In type theory, unlike set theory, objects are classified using a primitive notion of type, similar to the data-types used in programming languages. These elaborately structured types can be used to express detailed specifications of the objects classified, giving rise to principles of reasoning about these objects. To take a very simple example, the objects of a product type A×B are known to be of the form (a, b), and so one automatically knows how to construct them and how to decompose them. Similarly, an object of function type A → B can be acquired from an object of type B parametrized by objects of type A, and can be evaluated at an argument of type A. This rigidly predictable behavior of all objects (as opposed to set theory’s more liberal formation principles, allowing inhomogeneous sets) is one aspect of type theory that has led to its extensive use in verifying the correctness of computer programs. The clear reasoning principles associated with the construction of types also form the basis of modern computer proof assistants, which are used for formalizing mathematics and verifying the correctness of formalized proofs. We return to this aspect of type theory below.

One problem in understanding type theory from a mathematical point of view, however, has always been that the basic concept of type is unlike that of set in ways that have been hard to make precise. We believe that the new idea of regarding types, not as strange sets (perhaps constructed without using classical logic), but as spaces, viewed from the perspective of homotopy theory, is a significant step forward. In particular, it solves the problem of understanding how the notion of equality of elements of a type differs from that of elements of a set.

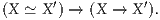

In homotopy theory one is concerned with spaces and continuous mappings between them, up to homotopy. A homotopy between a pair of continuous maps f : X → Y and g : X → Y is a continuous map H : X× [0, 1] → Y satisfying H(x, 0) = f(x) and H(x, 1) = g(x). The homotopy H may be thought of as a “continuous deformation” of f into g. The spaces X and Y are said to be homotopy equivalent, X ≃ Y, if there are continuous maps going back and forth, the composites of which are homotopical to the respective identity mappings, i.e., if they are isomorphic “up to homotopy”. Homotopy equivalent spaces have the same algebraic invariants (e.g., homology, or the fundamental group), and are said to have the same homotopy type.

Homotopy type theory (HoTT) interprets type theory from a homotopical perspective. In homotopy type theory, we regard the types as “spaces” (as studied in homotopy theory) or higher groupoids, and the logical constructions (such as the product A×B) as homotopy-invariant constructions on these spaces. In this way, we are able to manipulate spaces directly without first having to develop point-set topology (or any combinatorial replacement for it, such as the theory of simplicial sets). To briefly explain this perspective, consider first the basic concept of type theory, namely that the term a is of type A, which is written:

This expression is traditionally thought of as akin to:

“a is an element of the set A”.

However, in homotopy type theory we think of it instead as:

“a is a point of the space A”.

Similarly, every function f : A → B in type theory is regarded as a continuous map from the space A to the space B.

We should stress that these “spaces” are treated purely homotopically, not topologically. For instance, there is no notion of “open subset” of a type or of “convergence” of a sequence of elements of a type. We only have “homotopical” notions, such as paths between points and homotopies between paths, which also make sense in other models of homotopy theory (such as simplicial sets). Thus, it would be more accurate to say that we treat types as ∞-groupoids; this is a name for the “invariant objects” of homotopy theory which can be presented by topological spaces, simplicial sets, or any other model for homotopy theory. However, it is convenient to sometimes use topological words such as “space” and “path”, as long as we remember that other topological concepts are not applicable.

(It is tempting to also use the phrase homotopy type for these objects, suggesting the dual interpretation of “a type (as in type theory) viewed homotopically” and “a space considered from the point of view of homotopy theory”. The latter is a bit different from the classical meaning of “homotopy type” as an equivalence class of spaces modulo homotopy equivalence, although it does preserve the meaning of phrases such as “these two spaces have the same homotopy type”.)

The idea of interpreting types as structured objects, rather than sets, has a long pedigree, and is known to clarify various mysterious aspects of type theory. For instance, interpreting types as sheaves helps explain the intuitionistic nature of type-theoretic logic, while interpreting them as partial equivalence relations or “domains” helps explain its computational aspects. It also implies that we can use type-theoretic reasoning to study the structured objects, leading to the rich field of categorical logic. The homotopical interpretation fits this same pattern: it clarifies the nature of identity (or equality) in type theory, and allows us to use type-theoretic reasoning in the study of homotopy theory.

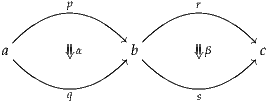

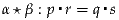

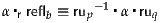

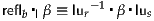

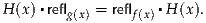

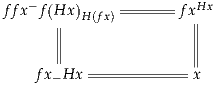

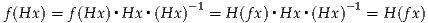

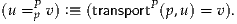

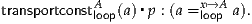

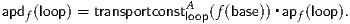

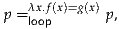

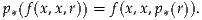

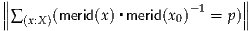

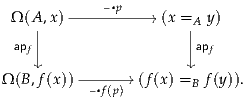

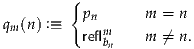

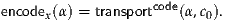

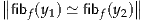

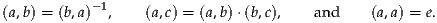

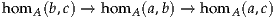

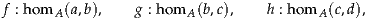

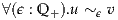

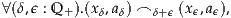

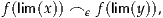

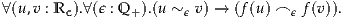

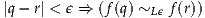

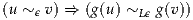

The key new idea of the homotopy interpretation is that the logical notion of identity a = b of two objects a, b : A of the same type A can be understood as the existence of a path p : a ↝ b from point a to point b in the space A. This also means that two functions f, g : A → B can be identified if they are homotopic, since a homotopy is just a (continuous) family of paths px : f(x) ↝ g(x) in B, one for each x : A. In type theory, for every type A there is a (formerly somewhat mysterious) type IdA of identifications of two objects of A; in homotopy type theory, this is just the path space AI of all continuous maps I → A from the unit interval. In this way, a term p : IdA(a, b) represents a path p : a ↝ b in A.

The idea of homotopy type theory arose around 2006 in independent work by Awodey and Warren [AW09] and Voevodsky [Voe06], but it was inspired by Hofmann and Streicher’s earlier groupoid interpretation [HS98]. Indeed, higher-dimensional category theory (particularly the theory of weak ∞-groupoids) is now known to be intimately connected to homotopy theory, as proposed by Grothendieck and now being studied intensely by mathematicians of both sorts. The original semantic models of Awodey–Warren and Voevodsky use well-known notions and techniques from homotopy theory which are now also in use in higher category theory, such as Quillen model categories and Kan simplicial sets.

Voevodsky recognized that the simplicial interpretation of type theory satisfies a further crucial property, dubbed univalence, which had not previously been considered in type theory (although Church’s principle of extensionality for propositions turns out to be a very special case of it). Adding univalence to type theory in the form of a new axiom has far-reaching consequences, many of which are natural, simplifying and compelling. The univalence axiom also further strengthens the homotopical view of type theory, since it holds in the simplicial model and other related models, while failing under the view of types as sets.

Very briefly, the basic idea of the univalence axiom can be explained

as follows. In type theory, one can have a universe  , the terms of

which are themselves types, A :

, the terms of

which are themselves types, A :  , etc. Those types that are terms of

, etc. Those types that are terms of  are commonly called small types. Like any type,

are commonly called small types. Like any type,  has an identity

type Id

has an identity

type Id , which expresses the identity relation A = B between small

types. Thinking of types as spaces,

, which expresses the identity relation A = B between small

types. Thinking of types as spaces,  is a space, the points of which are

spaces; to understand its identity type, we must ask, what is a path

p : A ↝ B between spaces in

is a space, the points of which are

spaces; to understand its identity type, we must ask, what is a path

p : A ↝ B between spaces in  ? The univalence axiom says that such paths

correspond to homotopy equivalences A ≃ B, (roughly) as explained above.

A bit more precisely, given any (small) types A and B, in addition

to the primitive type Id

? The univalence axiom says that such paths

correspond to homotopy equivalences A ≃ B, (roughly) as explained above.

A bit more precisely, given any (small) types A and B, in addition

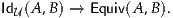

to the primitive type Id (A, B) of identifications of A with B, there

is the defined type Equiv(A, B) of equivalences from A to B. Since

the identity map on any object is an equivalence, there is a canonical

map,

(A, B) of identifications of A with B, there

is the defined type Equiv(A, B) of equivalences from A to B. Since

the identity map on any object is an equivalence, there is a canonical

map,

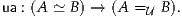

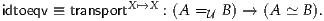

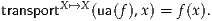

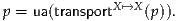

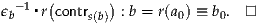

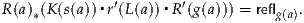

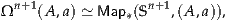

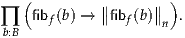

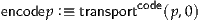

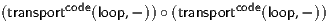

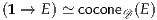

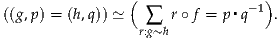

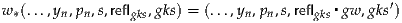

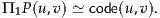

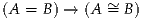

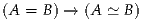

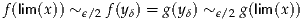

The univalence axiom states that this map is itself an equivalence. At the risk of oversimplifying, we can state this succinctly as follows:

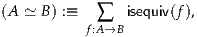

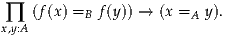

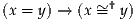

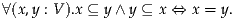

In other words, identity is equivalent to equivalence. In particular, one may say that “equivalent types are identical”. However, this phrase is somewhat misleading, since it may sound like a sort of “skeletality” condition which collapses the notion of equivalence to coincide with identity, whereas in fact univalence is about expanding the notion of identity so as to coincide with the (unchanged) notion of equivalence.

From the homotopical point of view, univalence implies that spaces of the

same homotopy type are connected by a path in the universe  , in accord

with the intuition of a classifying space for (small) spaces. From the

logical point of view, however, it is a radically new idea: it says that

isomorphic things can be identified! Mathematicians are of course used to

identifying isomorphic structures in practice, but they generally do

so by “abuse of notation”, or some other informal device, knowing

that the objects involved are not “really” identical. But in this new

foundational scheme, such structures can be formally identified, in the

logical sense that every property or construction involving one also

applies to the other. Indeed, the identification is now made explicit, and

properties and constructions can be systematically transported along it.

Moreover, the different ways in which such identifications may be

made themselves form a structure that one can (and should!) take into

account.

, in accord

with the intuition of a classifying space for (small) spaces. From the

logical point of view, however, it is a radically new idea: it says that

isomorphic things can be identified! Mathematicians are of course used to

identifying isomorphic structures in practice, but they generally do

so by “abuse of notation”, or some other informal device, knowing

that the objects involved are not “really” identical. But in this new

foundational scheme, such structures can be formally identified, in the

logical sense that every property or construction involving one also

applies to the other. Indeed, the identification is now made explicit, and

properties and constructions can be systematically transported along it.

Moreover, the different ways in which such identifications may be

made themselves form a structure that one can (and should!) take into

account.

Thus in sum, for points A and B of the universe  (i.e., small types), the

univalence axiom identifies the following three notions:

(i.e., small types), the

univalence axiom identifies the following three notions:

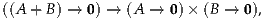

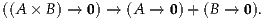

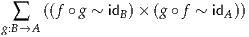

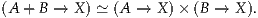

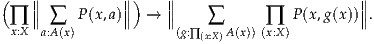

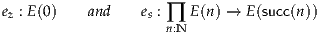

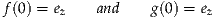

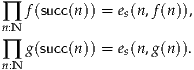

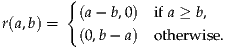

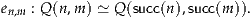

One of the classical advantages of type theory is its simple and effective techniques for working with inductively defined structures. The simplest nontrivial inductively defined structure is the natural numbers, which is inductively generated by zero and the successor function. From this statement one can algorithmically extract the principle of mathematical induction, which characterizes the natural numbers. More general inductive definitions encompass lists and well-founded trees of all sorts, each of which is characterized by a corresponding “induction principle”. This includes most data structures used in certain programming languages; hence the usefulness of type theory in formal reasoning about the latter. If conceived in a very general sense, inductive definitions also include examples such as a disjoint union A + B, which may be regarded as “inductively” generated by the two injections A → A + B and B → A + B. The “induction principle” in this case is “proof by case analysis”, which characterizes the disjoint union.

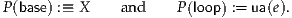

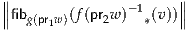

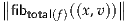

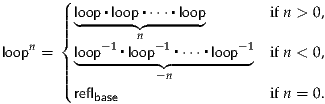

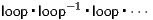

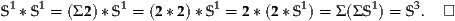

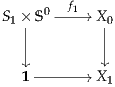

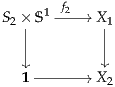

In homotopy theory, it is natural to consider also “inductively defined spaces” which are generated not merely by a collection of points, but also by collections of paths and higher paths. Classically, such spaces are called CW complexes. For instance, the circle S1 is generated by a single point and a single path from that point to itself. Similarly, the 2-sphere S2 is generated by a single point b and a single two-dimensional path from the constant path at b to itself, while the torus T2 is generated by a single point, two paths p and q from that point to itself, and a two-dimensional path from p▪q to q▪p.

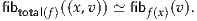

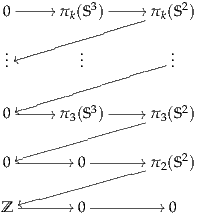

By using the identification of paths with identities in homotopy type theory, these sort of “inductively defined spaces” can be characterized in type theory by “induction principles”, entirely analogously to classical examples such as the natural numbers and the disjoint union. The resulting higher inductive types give a direct “logical” way to reason about familiar spaces such as spheres, which (in combination with univalence) can be used to perform familiar arguments from homotopy theory, such as calculating homotopy groups of spheres, in a purely formal way. The resulting proofs are a marriage of classical homotopy-theoretic ideas with classical type-theoretic ones, yielding new insight into both disciplines.

Moreover, this is only the tip of the iceberg: many abstract constructions from homotopy theory, such as homotopy colimits, suspensions, Postnikov towers, localization, completion, and spectrification, can also be expressed as higher inductive types. Many of these are classically constructed using Quillen’s “small object argument”, which can be regarded as a finite way of algorithmically describing an infinite CW complex presentation of a space, just as “zero and successor” is a finite algorithmic description of the infinite set of natural numbers. Spaces produced by the small object argument are infamously complicated and difficult to understand; the type-theoretic approach is potentially much simpler, bypassing the need for any explicit construction by giving direct access to the appropriate “induction principle”. Thus, the combination of univalence and higher inductive types suggests the possibility of a revolution, of sorts, in the practice of homotopy theory.

We have claimed that univalent foundations can eventually serve as a foundation for “all” of mathematics, but so far we have discussed only homotopy theory. Of course, there are many specific examples of the use of type theory without the new homotopy type theory features to formalize mathematics, such as the recent formalization of the Feit–Thompson odd-order theorem in Coq [GAA+13].

But the traditional view is that mathematics is founded on set theory, in the sense that all mathematical objects and constructions can be coded into a theory such as Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory (ZF). However, it is well-established by now that for most mathematics outside of set theory proper, the intricate hierarchical membership structure of sets in ZF is really unnecessary: a more “structural” theory, such as Lawvere’s Elementary Theory of the Category of Sets [Law05], suffices.

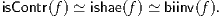

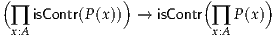

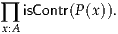

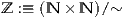

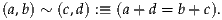

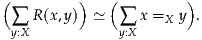

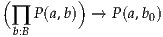

In univalent foundations, the basic objects are “homotopy types” rather than sets, but we can define a class of types which behave like sets. Homotopically, these can be thought of as spaces in which every connected component is contractible, i.e. those which are homotopy equivalent to a discrete space. It is a theorem that the category of such “sets” satisfies Lawvere’s axioms (or related ones, depending on the details of the theory). Thus, any sort of mathematics that can be represented in an ETCS-like theory (which, experience suggests, is essentially all of mathematics) can equally well be represented in univalent foundations.

This supports the claim that univalent foundations is at least as good as existing foundations of mathematics. A mathematician working in univalent foundations can build structures out of sets in a familiar way, with more general homotopy types waiting in the foundational background until there is need of them. For this reason, most of the applications in this book have been chosen to be areas where univalent foundations has something new to contribute that distinguishes it from existing foundational systems.

Unsurprisingly, homotopy theory and category theory are two of these, but perhaps less obvious is that univalent foundations has something new and interesting to offer even in subjects such as set theory and real analysis. For instance, the univalence axiom allows us to identify isomorphic structures, while higher inductive types allow direct descriptions of objects by their universal properties. Thus we can generally avoid resorting to arbitrarily chosen representatives or transfinite iterative constructions. In fact, even the objects of study in ZF set theory can be characterized, inside the sets of univalent foundations, by such an inductive universal property.

One difficulty often encountered by the classical mathematician when faced with learning about type theory is that it is usually presented as a fully or partially formalized deductive system. This style, which is very useful for proof-theoretic investigations, is not particularly convenient for use in applied, informal reasoning. Nor is it even familiar to most working mathematicians, even those who might be interested in foundations of mathematics. One objective of the present work is to develop an informal style of doing mathematics in univalent foundations that is at once rigorous and precise, but is also closer to the language and style of presentation of everyday mathematics.

In present-day mathematics, one usually constructs and reasons about mathematical objects in a way that could in principle, one presumes, be formalized in a system of elementary set theory, such as ZFC — at least given enough ingenuity and patience. For the most part, one does not even need to be aware of this possibility, since it largely coincides with the condition that a proof be “fully rigorous” (in the sense that all mathematicians have come to understand intuitively through education and experience). But one does need to learn to be careful about a few aspects of “informal set theory”: the use of collections too large or inchoate to be sets; the axiom of choice and its equivalents; even (for undergraduates) the method of proof by contradiction; and so on. Adopting a new foundational system such as homotopy type theory as the implicit formal basis of informal reasoning will require adjusting some of one’s instincts and practices. The present text is intended to serve as an example of this “new kind of mathematics”, which is still informal, but could now in principle be formalized in homotopy type theory, rather than ZFC, again given enough ingenuity and patience.

It is worth emphasizing that, in this new system, such formalization can have real practical benefits. The formal system of type theory is suited to computer systems and has been implemented in existing proof assistants. A proof assistant is a computer program which guides the user in construction of a fully formal proof, only allowing valid steps of reasoning. It also provides some degree of automation, can search libraries for existing theorems, and can even extract numerical algorithms from the resulting (constructive) proofs.

We believe that this aspect of the univalent foundations program distinguishes it from other approaches to foundations, potentially providing a new practical utility for the working mathematician. Indeed, proof assistants based on older type theories have already been used to formalize substantial mathematical proofs, such as the four-color theorem and the Feit–Thompson theorem. Computer implementations of univalent foundations are presently works in progress (like the theory itself). However, even its currently available implementations (which are mostly small modifications to existing proof assistants such as Coq and Agda) have already demonstrated their worth, not only in the formalization of known proofs, but in the discovery of new ones. Indeed, many of the proofs described in this book were actually first done in a fully formalized form in a proof assistant, and are only now being “unformalized” for the first time — a reversal of the usual relation between formal and informal mathematics.

One can imagine a not-too-distant future when it will be possible for mathematicians to verify the correctness of their own papers by working within the system of univalent foundations, formalized in a proof assistant, and that doing so will become as natural as typesetting their own papers in TEX. In principle, this could be equally true for any other foundational system, but we believe it to be more practically attainable using univalent foundations, as witnessed by the present work and its formal counterpart.

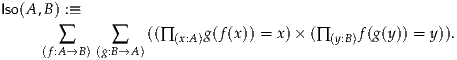

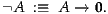

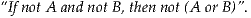

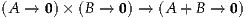

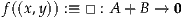

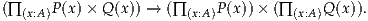

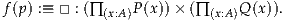

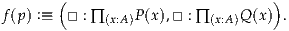

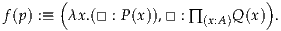

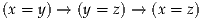

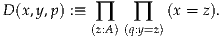

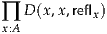

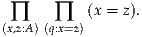

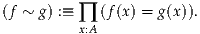

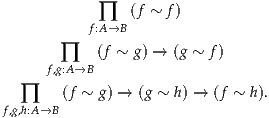

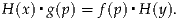

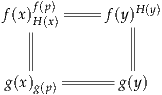

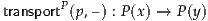

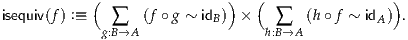

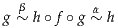

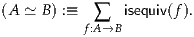

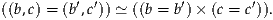

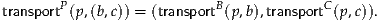

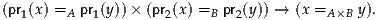

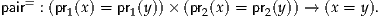

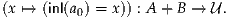

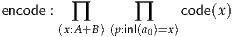

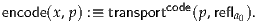

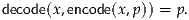

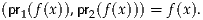

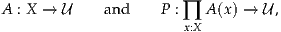

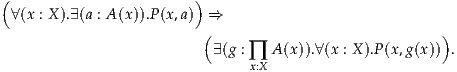

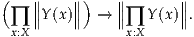

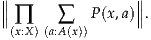

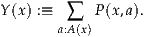

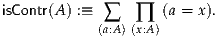

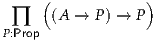

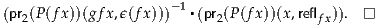

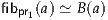

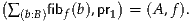

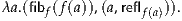

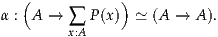

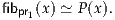

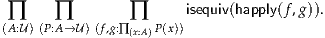

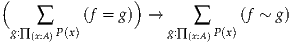

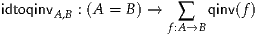

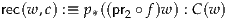

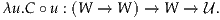

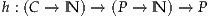

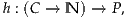

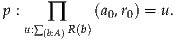

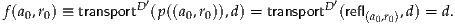

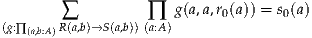

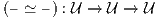

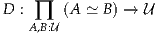

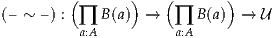

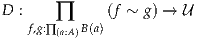

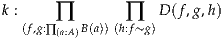

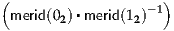

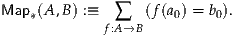

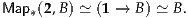

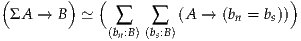

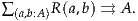

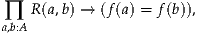

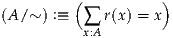

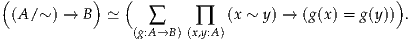

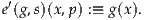

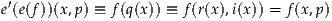

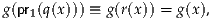

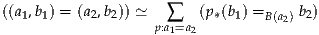

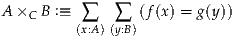

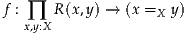

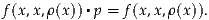

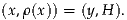

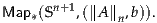

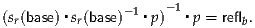

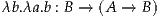

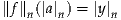

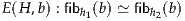

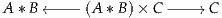

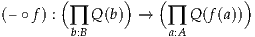

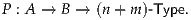

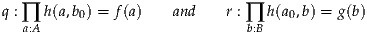

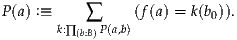

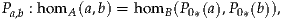

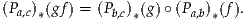

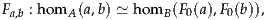

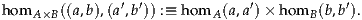

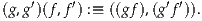

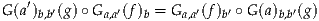

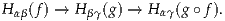

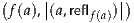

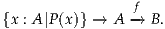

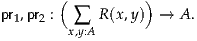

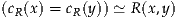

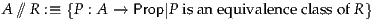

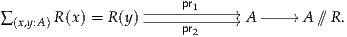

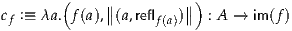

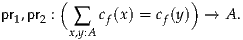

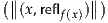

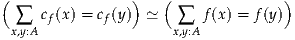

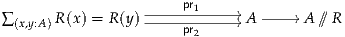

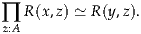

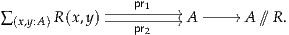

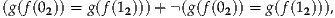

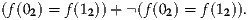

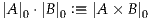

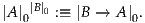

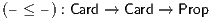

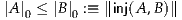

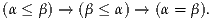

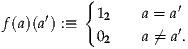

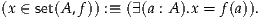

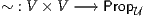

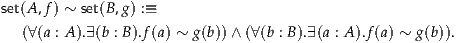

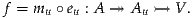

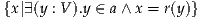

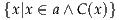

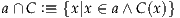

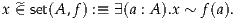

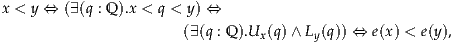

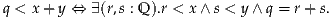

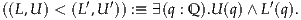

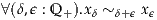

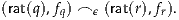

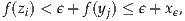

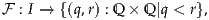

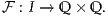

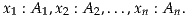

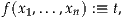

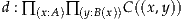

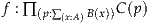

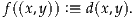

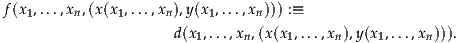

One of the most striking differences between classical foundations and type theory is the idea of proof relevance, according to which mathematical statements, and even their proofs, become first-class mathematical objects. In type theory, we represent mathematical statements by types, which can be regarded simultaneously as both mathematical constructions and mathematical assertions, a conception also known as propositions as types. Accordingly, we can regard a term a : A as both an element of the type A (or in homotopy type theory, a point of the space A), and at the same time, a proof of the proposition A. To take an example, suppose we have sets A and B (discrete spaces), and consider the statement “A is isomorphic to B”. In type theory, this can be rendered as:

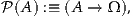

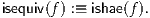

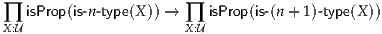

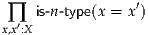

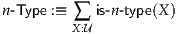

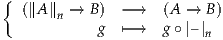

The logic of propositions-as-types is flexible and supports many variations, such as using only a subclass of types to represent propositions. In homotopy type theory, there are natural such subclasses arising from the fact that the system of all types, just like spaces in classical homotopy theory, is “stratified” according to the dimensions in which their higher homotopy structure exists or collapses. In particular, Voevodsky has found a purely type-theoretic definition of homotopy n-types, corresponding to spaces with no nontrivial homotopy information above dimension n. (The 0-types are the “sets” mentioned previously as satisfying Lawvere’s axioms.) Moreover, with higher inductive types, we can universally “truncate” a type into an n-type; in classical homotopy theory this would be its nth Postnikov section. Particularly important for logic is the case of homotopy (-1)-types, which we call mere propositions. Classically, every (-1)-type is empty or contractible; we interpret these possibilities as the truth values “false” and “true” respectively.

Using all types as propositions yields a “constructive” conception of logic (for more on which, see [Kol32, TvD88a, TvD88b]), which gives type theory its good computational character. For instance, every proof that something exists carries with it enough information to actually find such an object; and from a proof that “A or B” holds, one can extract either a proof that A holds or one that B holds. Thus, from every proof we can automatically extract an algorithm; this can be very useful in applications to computer programming.

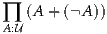

However, this logic does not faithfully represent certain important classical principles of reasoning, such as the axiom of choice and the law of excluded middle. For these we need to use the “(-1)-truncated” logic, in which only the homotopy (-1)-types represent propositions; and under this interpretation, the system is fully compatible with classical mathematics. Homotopy type theory is thus compatible with both constructive and classical conceptions of logic, and many more besides.

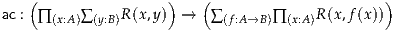

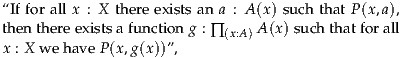

More specifically, consider on one hand the axiom of choice: “if for every x : A there exists a y : B such that R(x, y), there is a function f : A → B such that for all x : A we have R(x, f(x)).” The pure propositions-as-types notion of “there exists” is strong enough to make this statement simply provable — yet it does not have all the consequences of the usual axiom of choice. However, in (-1)-truncated logic, this statement is not automatically true, but is a strong assumption with the same sorts of consequences as its counterpart in classical set theory.

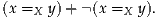

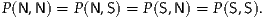

On the other hand, consider the law of excluded middle: “for all A, either A or not A.” Interpreting this in the pure propositions-as-types logic yields a statement that is inconsistent with the univalence axiom. For since proving “A” means exhibiting an element of it, this assumption would give a uniform way of selecting an element from every nonempty type — a sort of Hilbertian choice operator. Univalence implies that the element of A selected by such a choice operator must be invariant under all self-equivalences of A, since these are identified with self-identities and every operation must respect identity; but clearly some types have automorphisms with no fixed points, e.g. we can swap the elements of a two-element type. However, the “(-1)-truncated law of excluded middle”, though also not automatically true, may consistently be assumed with most of the same consequences as in classical mathematics.

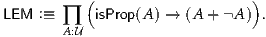

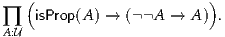

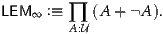

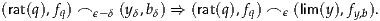

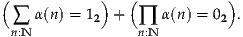

In other words, while the pure propositions-as-types logic is “constructive” in the strong algorithmic sense mentioned above, the default (-1)-truncated logic is “constructive” in a different sense (namely, that of the logic formalized by Heyting under the name “intuitionistic”); and to the latter we may freely add the axioms of choice and excluded middle to obtain a logic that may be called “classical”. Thus, the homotopical perspective reveals that classical and constructive logic can coexist, as endpoints of a spectrum of different systems, with an infinite number of possibilities in between (the homotopy n-types for -1 < n < ∞). We may speak of “LEMn” and “ACn”, with AC∞ being provable and LEM∞ inconsistent with univalence, while AC-1 and LEM-1 are the versions familiar to classical mathematicians (hence in most cases it is appropriate to assume the subscript (-1) when none is given). Indeed, one can even have useful systems in which only certain types satisfy such further “classical” principles, while types in general remain “constructive”.

It is worth emphasizing that univalent foundations does not require the use of constructive or intuitionistic logic. Most of classical mathematics which depends on the law of excluded middle and the axiom of choice can be performed in univalent foundations, simply by assuming that these two principles hold (in their proper, (-1)-truncated, form). However, type theory does encourage avoiding these principles when they are unnecessary, for several reasons.

First of all, every mathematician knows that a theorem is more powerful when proven using fewer assumptions, since it applies to more examples. The situation with AC and LEM is no different: type theory admits many interesting “nonstandard” models, such as in sheaf toposes, where classicality principles such as AC and LEM tend to fail. Homotopy type theory admits similar models in higher toposes, such as are studied in [TV02, Rez05, Lur09]. Thus, if we avoid using these principles, the theorems we prove will be valid internally to all such models.

Secondly, one of the additional virtues of type theory is its computable character. In addition to being a foundation for mathematics, type theory is a formal theory of computation, and can be treated as a powerful programming language. From this perspective, the rules of the system cannot be chosen arbitrarily the way set-theoretic axioms can: there must be a harmony between them which allows all proofs to be “executed” as programs. We do not yet fully understand the new principles introduced by homotopy type theory, such as univalence and higher inductive types, from this point of view, but the basic outlines are emerging; see, for example, [LH12]. It has been known for a long time, however, that principles such as AC and LEM are fundamentally antithetical to computability, since they assert baldly that certain things exist without giving any way to compute them. Thus, avoiding them is necessary to maintain the character of type theory as a theory of computation.

Fortunately, constructive reasoning is not as hard as it may seem. In some cases, simply by rephrasing some definitions, a theorem can be made constructive and its proof more elegant. Moreover, in univalent foundations this seems to happen more often. For instance:

Of course, these simplifications could as well be taken as evidence that the new methods will not, ultimately, prove to be really constructive. However, we emphasize again that the reader does not have to care, or worry, about constructivity in order to read this book. The point is that in all of the above examples, the version of the theory we give has independent advantages, whether or not LEM and AC are assumed to be available. Constructivity, if attained, will be an added bonus.

Given this discussion of adding new principles such as univalence, higher inductive types, AC, and LEM, one may wonder whether the resulting system remains consistent. (One of the original virtues of type theory, relative to set theory, was that it can be seen to be consistent by proof-theoretic means). As with any foundational system, consistency is a relative question: “consistent with respect to what?” The short answer is that all of the constructions and axioms considered in this book have a model in the category of Kan complexes, due to Voevodsky [KLV12] (see [LS13b] for higher inductive types). Thus, they are known to be consistent relative to ZFC (with as many inaccessible cardinals as we need nested univalent universes). Giving a more traditionally type-theoretic account of this consistency is work in progress (see, e.g., [LH12, BCH13]).

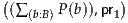

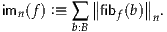

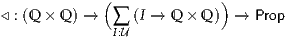

We summarize the different points of view of the type-theoretic operations in Table 1.

| Types | Logic | Sets | Homotopy | |

| A | proposition | set | space | |

| a : A | proof | element | point | |

| B(x) | predicate | family of sets | fibration | |

| b(x) : B(x) | conditional proof | family of elements | section | |

| 0, 1 | ⊥, ⊤ | ∅, {∅} | ∅, * | |

| A+ B | A∨B | disjoint union | coproduct | |

| A×B | A∧B | set of pairs | product space | |

| A →B | A ⇒B | set of functions | function space | |

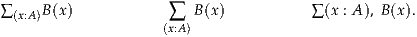

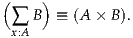

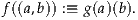

| ∑(x:A) B(x) | ∃x:AB(x) | disjoint sum | total space | |

| ∏(x:A) B(x) | ∀x:AB(x) | product | space of sections | |

| IdA | equality = |  x ∈A} x ∈A} | path space AI | |

For those interested in contributing to this new branch of mathematics, it may be encouraging to know that there are many interesting open questions.

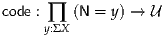

Perhaps the most pressing of them is the “constructivity” of the Univalence Axiom, posed by Voevodsky in [Voe12]. The basic system of type theory follows the structure of Gentzen’s natural deduction. Logical connectives are defined by their introduction rules, and have elimination rules justified by computation rules. Following this pattern, and using Tait’s computability method, originally designed to analyse Gödel’s Dialectica interpretation, one can show the property of normalization for type theory. This in turn implies important properties such as decidability of type-checking (a crucial property since type-checking corresponds to proof-checking, and one can argue that we should be able to “recognize a proof when we see one”), and the so-called “canonicity property” that any closed term of the type of natural numbers reduces to a numeral. This last property, and the uniform structure of introduction/elimination rules, are lost when one extends type theory with an axiom, such as the axiom of function extensionality, or the univalence axiom. Voevodsky has formulated a precise mathematical conjecture connected to this question of canonicity for type theory extended with the axiom of Univalence: given a closed term of the type of natural numbers, is it always possible to find a numeral and a proof that this term is equal to this numeral, where this proof of equality may itself use the univalence axiom? More generally, an important issue is whether it is possible to provide a constructive justification of the univalence axiom. What about if one adds other homotopically motivated constructions, like higher inductive types? These questions remain open at the present time, although methods are currently being developed to try to find answers.

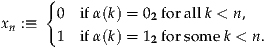

Another basic issue is the difficulty of working with types, such as the natural numbers, that are essentially sets (i.e., discrete spaces), containing only trivial paths. At present, homotopy type theory can really only characterize spaces up to homotopy equivalence, which means that these “discrete spaces” may only be homotopy equivalent to discrete spaces. Type-theoretically, this means there are many paths that are equal to reflexivity, but not judgmentally equal to it (see §1.1 for the meaning of “judgmentally”). While this homotopy-invariance has advantages, these “meaningless” identity terms do introduce needless complications into arguments and constructions, so it would be convenient to have a systematic way of eliminating or collapsing them.

A more specialized, but no less important, problem is the relation between homotopy type theory and the research on higher toposes currently happening at the intersection of higher category theory and homotopy theory. There is a growing conviction among those familiar with both subjects that they are intimately connected. For instance, the notion of a univalent universe should coincide with that of an object classifier, while higher inductive types should be an “elementary” reflection of local presentability. More generally, homotopy type theory should be the “internal language” of (∞, 1)-toposes, just as intuitionistic higher-order logic is the internal language of ordinary 1-toposes. Despite this general consensus, however, details remain to be worked out — in particular, questions of coherence and strictness remain to be addressed — and doing so will undoubtedly lead to further insights into both concepts.

But by far the largest field of work to be done is in the ongoing formalization of everyday mathematics in this new system. Recent successes in formalizing some facts from basic homotopy theory and category theory have been encouraging; some of these are described in Chapters 8 and 9. Obviously, however, much work remains to be done.

The homotopy type theory community maintains a web site and group blog at http://homotopytypetheory.org, as well as a discussion email list. Newcomers are always welcome!

This book is divided into two parts. Part I, “Foundations”, develops the fundamental concepts of homotopy type theory. This is the mathematical foundation on which the development of specific subjects is built, and which is required for the understanding of the univalent foundations approach. To a programmer, this is “library code”. Since univalent foundations is a new and different kind of mathematics, its basic notions take some getting used to; thus Part I is fairly extensive.

Part II, “Mathematics”, consists of four chapters that build on the basic notions of Part I to exhibit some of the new things we can do with univalent foundations in four different areas of mathematics: homotopy theory (Chapter 8), category theory (Chapter 9), set theory (Chapter 10), and real analysis (Chapter 11). The chapters in Part II are more or less independent of each other, although occasionally one will use a lemma proven in another.

A reader who wants to seriously understand univalent foundations, and be able to work in it, will eventually have to read and understand most of Part I. However, a reader who just wants to get a taste of univalent foundations and what it can do may understandably balk at having to work through over 200 pages before getting to the “meat” in Part II. Fortunately, not all of Part I is necessary in order to read the chapters in Part II. Each chapter in Part II begins with a brief overview of its subject, what univalent foundations has to contribute to it, and the necessary background from Part I, so the courageous reader can turn immediately to the appropriate chapter for their favorite subject. For those who want to understand one or more chapters in Part II more deeply than this, but are not ready to read all of Part I, we provide here a brief summary of Part I, with remarks about which parts are necessary for which chapters in Part II.

Chapter 1 is about the basic notions of type theory, prior to any homotopical interpretation. A reader who is familiar with Martin-Löf type theory can quickly skim it to pick up the particulars of the theory we are using. However, readers without experience in type theory will need to read Chapter 1, as there are many subtle differences between type theory and other foundations such as set theory.

Chapter 2 introduces the homotopical viewpoint on type theory, along with the basic notions supporting this view, and describes the homotopical behavior of each component of the type theory from Chapter 1. It also introduces the univalence axiom (§2.10) — the first of the two basic innovations of homotopy type theory. Thus, it is quite basic and we encourage everyone to read it, especially §§2.1–2.4.

Chapter 3 describes how we represent logic in homotopy type theory, and its connection to classical logic as well as to constructive and intuitionistic logic. Here we define the law of excluded middle, the axiom of choice, and the axiom of propositional resizing (although, for the most part, we do not need to assume any of these in the rest of the book), as well as the propositional truncation which is essential for representing traditional logic. This chapter is essential background for Chapters 10 and 11, less important for Chapter 9, and not so necessary for Chapter 8.

Chapters 4 and 5 study two special topics in detail: equivalences (and related notions) and generalized inductive definitions. While these are important subjects in their own rights and provide a deeper understanding of homotopy type theory, for the most part they are not necessary for Part II. Only a few lemmas from Chapter 4 are used here and there, while the general discussions in §§5.1, 5.6 and 5.7 are helpful for providing the intuition required for Chapter 6. The generalized sorts of inductive definition discussed in §5.7 are also used in a few places in Chapters 10 and 11.

Chapter 6 introduces the second basic innovation of homotopy type theory — higher inductive types — with many examples. Higher inductive types are the primary object of study in Chapter 8, and some particular ones play important roles in Chapters 10 and 11. They are not so necessary for Chapter 9, although one example is used in §9.9.

Finally, Chapter 7 discusses homotopy n-types and related notions such as n-connected types. These notions are important for Chapter 8, but not so important in the rest of Part II, although the case n = -1 of some of the lemmas are used in §10.1.

This completes Part I. As mentioned above, Part II consists of four largely unrelated chapters, each describing what univalent foundations has to offer to a particular subject.

Of the chapters in Part II, Chapter 8 (Homotopy theory) is perhaps the most radical. Univalent foundations has a very different “synthetic” approach to homotopy theory in which homotopy types are the basic objects (namely, the types) rather than being constructed using topological spaces or some other set-theoretic model. This enables new styles of proof for classical theorems in algebraic topology, of which we present a sampling, from π1(S1) = Z to the Freudenthal suspension theorem.

In Chapter 9 (Category theory), we develop some basic (1-)category theory, adhering to the principle of the univalence axiom that equality is isomorphism. This has the pleasant effect of ensuring that all definitions and constructions are automatically invariant under equivalence of categories: indeed, equivalent categories are equal just as equivalent types are equal. (It also has connections to higher category theory and higher topos theory.)

Chapter 10 (Set theory) studies sets in univalent foundations. The category of sets has its usual properties, hence provides a foundation for any mathematics that doesn’t need homotopical or higher-categorical structures. We also observe that univalence makes cardinal and ordinal numbers a bit more pleasant, and that higher inductive types yield a cumulative hierarchy satisfying the usual axioms of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory.

In Chapter 11 (Real numbers), we summarize the construction of Dedekind real numbers, and then observe that higher inductive types allow a definition of Cauchy real numbers that avoids some associated problems in constructive mathematics. Then we sketch a similar approach to Conway’s surreal numbers.

Each chapter in this book ends with a Notes section, which collects historical comments, references to the literature, and attributions of results, to the extent possible. We have also included Exercises at the end of each chapter, to assist the reader in gaining familiarity with doing mathematics in univalent foundations.

Finally, recall that this book was written as a massively collaborative effort by a large number of people. We have done our best to achieve consistency in terminology and notation, and to put the mathematics in a linear sequence that flows logically, but it is very likely that some imperfections remain. We ask the reader’s forgiveness for any such infelicities, and welcome suggestions for improvement of the next edition. Part I Foundations

Homotopy type theory is (among other things) a foundational language for mathematics, i.e., an alternative to Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory. However, it behaves differently from set theory in several important ways, and that can take some getting used to. Explaining these differences carefully requires us to be more formal here than we will be in the rest of the book. As stated in the introduction, our goal is to write type theory informally; but for a mathematician accustomed to set theory, more precision at the beginning can help avoid some common misconceptions and mistakes.

We note that a set-theoretic foundation has two “layers”: the deductive system of first-order logic, and, formulated inside this system, the axioms of a particular theory, such as ZFC. Thus, set theory is not only about sets, but rather about the interplay between sets (the objects of the second layer) and propositions (the objects of the first layer).

By contrast, type theory is its own deductive system: it need not be formulated inside any superstructure, such as first-order logic. Instead of the two basic notions of set theory, sets and propositions, type theory has one basic notion: types. Propositions (statements which we can prove, disprove, assume, negate, and so on1 ) are identified with particular types, via the correspondence shown in Table 1 on page 18. Thus, the mathematical activity of proving a theorem is identified with a special case of the mathematical activity of constructing an object—in this case, an inhabitant of a type that represents a proposition.

This leads us to another difference between type theory and set theory, but to explain it we must say a little about deductive systems in general. Informally, a deductive system is a collection of rules for deriving things called judgments. If we think of a deductive system as a formal game, then the judgments are the “positions” in the game which we reach by following the game rules. We can also think of a deductive system as a sort of algebraic theory, in which case the judgments are the elements (like the elements of a group) and the deductive rules are the operations (like the group multiplication). From a logical point of view, the judgments can be considered to be the “external” statements, living in the metatheory, as opposed to the “internal” statements of the theory itself.

In the deductive system of first-order logic (on which set theory is based), there is only one kind of judgment: that a given proposition has a proof. That is, each proposition A gives rise to a judgment “A has a proof”, and all judgments are of this form. A rule of first-order logic such as “from A and B infer A∧B” is actually a rule of “proof construction” which says that given the judgments “A has a proof” and “B has a proof”, we may deduce that “A∧B has a proof”. Note that the judgment “A has a proof” exists at a different level from the proposition A itself, which is an internal statement of the theory.

The basic judgment of type theory, analogous to “A has a proof”, is written “a : A” and pronounced as “the term a has type A”, or more loosely “a is an element of A” (or, in homotopy type theory, “a is a point of A”). When A is a type representing a proposition, then a may be called a witness to the provability of A, or evidence of the truth of A (or even a proof of A, but we will try to avoid this confusing terminology). In this case, the judgment a : A is derivable in type theory (for some a) precisely when the analogous judgment “A has a proof” is derivable in first-order logic (modulo differences in the axioms assumed and in the encoding of mathematics, as we will discuss throughout the book).

On the other hand, if the type A is being treated more like a set than like a proposition (although as we will see, the distinction can become blurry), then “a : A” may be regarded as analogous to the set-theoretic statement “a ∈ A”. However, there is an essential difference in that “a : A” is a judgment whereas “a ∈ A” is a proposition. In particular, when working internally in type theory, we cannot make statements such as “if a : A then it is not the case that b : B”, nor can we “disprove” the judgment “a : A”.

A good way to think about this is that in set theory, “membership” is a relation which may or may not hold between two pre-existing objects “a” and “A”, while in type theory we cannot talk about an element “a” in isolation: every element by its very nature is an element of some type, and that type is (generally speaking) uniquely determined. Thus, when we say informally “let x be a natural number”, in set theory this is shorthand for “let x be a thing and assume that x ∈N”, whereas in type theory “let x : N” is an atomic statement: we cannot introduce a variable without specifying its type.

At first glance, this may seem an uncomfortable restriction, but it is arguably closer to the intuitive mathematical meaning of “let x be a natural number”. In practice, it seems that whenever we actually need “a ∈ A” to be a proposition rather than a judgment, there is always an ambient set B of which a is known to be an element and A is known to be a subset. This situation is also easy to represent in type theory, by taking a to be an element of the type B, and A to be a predicate on B; see §3.5.

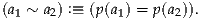

A last difference between type theory and set theory is the treatment of equality. The familiar notion of equality in mathematics is a proposition: e.g. we can disprove an equality or assume an equality as a hypothesis. Since in type theory, propositions are types, this means that equality is a type: for elements a, b : A (that is, both a : A and b : A) we have a type “a =A b”. (In homotopy type theory, of course, this equality proposition can behave in unfamiliar ways: see §1.12 and Chapter 2, and the rest of the book). When a =A b is inhabited, we say that a and b are (propositionally) equal.

However, in type theory there is also a need for an equality judgment, existing at the same level as the judgment “x : A”. This is called judgmental equality or definitional equality, and we write it as a ≡ b : A or simply a ≡ b. It is helpful to think of this as meaning “equal by definition”. For instance, if we define a function f : N →N by the equation f(x) = x2, then the expression f(3) is equal to 32 by definition. Inside the theory, it does not make sense to negate or assume an equality-by-definition; we cannot say “if x is equal to y by definition, then z is not equal to w by definition”. Whether or not two expressions are equal by definition is just a matter of expanding out the definitions; in particular, it is algorithmically decidable (though the algorithm is necessarily meta-theoretic, not internal to the theory).

As type theory becomes more complicated, judgmental equality can get more subtle than this, but it is a good intuition to start from. Alternatively, if we regard a deductive system as an algebraic theory, then judgmental equality is simply the equality in that theory, analogous to the equality between elements of a group—the only potential for confusion is that there is also an object inside the deductive system of type theory (namely the type “a = b”) which behaves internally as a notion of “equality”.

The reason we want a judgmental notion of equality is so that it can control the other form of judgment, “a : A”. For instance, suppose we have given a proof that 32 = 9, i.e. we have derived the judgment p : (32 = 9) for some p. Then the same witness p ought to count as a proof that f(3) = 9, since f(3) is 32 by definition. The best way to represent this is with a rule saying that given the judgments a : A and A ≡ B, we may derive the judgment a : B.

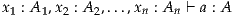

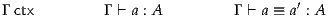

Thus, for us, type theory will be a deductive system based on two forms of judgment:

| Judgment | Meaning |

| a : A | “a is an object of type A” |

| a ≡ b : A | “a and b are definitionally equal objects of type A” |

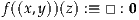

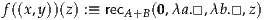

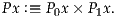

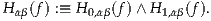

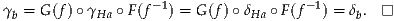

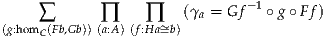

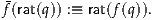

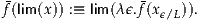

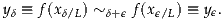

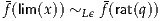

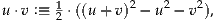

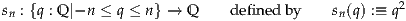

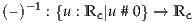

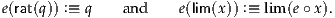

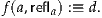

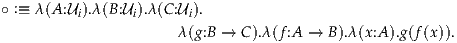

When introducing a definitional equality, i.e., defining one thing to be equal to another, we will use the symbol “:≡”. Thus, the above definition of the function f would be written as f(x) :≡ x2.

Because judgments cannot be put together into more complicated statements, the symbols “:” and “≡” bind more loosely than anything else.2 Thus, for instance, “p : x = y” should be parsed as “p : (x = y)”, which makes sense since “x = y” is a type, and not as “(p : x) = y”, which is senseless since “p : x” is a judgment and cannot be equal to anything. Similarly, “A ≡ x = y” can only be parsed as “A ≡ (x = y)”, although in extreme cases such as this, one ought to add parentheses anyway to aid reading comprehension. Moreover, later on we will fall into the common notation of chaining together equalities — e.g. writing a = b = c = d to mean “a = b and b = c and c = d, hence a = d” — and we will also include judgmental equalities in such chains. Context usually suffices to make the intent clear.

This is perhaps also an appropriate place to mention that the common mathematical notation “f : A → B”, expressing the fact that f is a function from A to B, can be regarded as a typing judgment, since we use “A → B” as notation for the type of functions from A to B (as is standard practice in type theory; see §1.4).

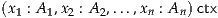

Judgments may depend on assumptions of the form x : A, where x is a variable and A is a type. For example, we may construct an object m + n : N under the assumptions that m, n : N. Another example is that assuming A is a type, x, y : A, and p : x =A y, we may construct an element p-1 : y =A x. The collection of all such assumptions is called the context; from a topological point of view it may be thought of as a “parameter space”. In fact, technically the context must be an ordered list of assumptions, since later assumptions may depend on previous ones: the assumption x : A can only be made after the assumptions of any variables appearing in the type A.

If the type A in an assumption x : A represents a proposition, then the assumption is a type-theoretic version of a hypothesis: we assume that the proposition A holds. When types are regarded as propositions, we may omit the names of their proofs. Thus, in the second example above we may instead say that assuming x =A y, we can prove y =A x. However, since we are doing “proof-relevant” mathematics, we will frequently refer back to proofs as objects. In the example above, for instance, we may want to establish that p-1 together with the proofs of transitivity and reflexivity behave like a groupoid; see Chapter 2.

Note that under this meaning of the word assumption, we can assume a propositional equality (by assuming a variable p : x = y), but we cannot assume a judgmental equality x ≡ y, since it is not a type that can have an element. However, we can do something else which looks kind of like assuming a judgmental equality: if we have a type or an element which involves a variable x : A, then we can substitute any particular element a : A for x to obtain a more specific type or element. We will sometimes use language like “now assume x ≡ a” to refer to this process of substitution, even though it is not an assumption in the technical sense introduced above.

By the same token, we cannot prove a judgmental equality either, since it is not a type in which we can exhibit a witness. Nevertheless, we will sometimes state judgmental equalities as part of a theorem, e.g. “there exists f : A → B such that f(x) ≡ y”. This should be regarded as the making of two separate judgments: first we make the judgment f : A → B for some element f, then we make the additional judgment that f(x) ≡ y.

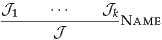

In the rest of this chapter, we attempt to give an informal presentation of type theory, sufficient for the purposes of this book; we give a more formal account in Appendix A. Aside from some fairly obvious rules (such as the fact that judgmentally equal things can always be substituted for each other), the rules of type theory can be grouped into type formers. Each type former consists of a way to construct types (possibly making use of previously constructed types), together with rules for the construction and behavior of elements of that type. In most cases, these rules follow a fairly predictable pattern, but we will not attempt to make this precise here; see however the beginning of §1.5 and also Chapter 5.

An important aspect of the type theory presented in this chapter is that it consists entirely of rules, without any axioms. In the description of deductive systems in terms of judgments, the rules are what allow us to conclude one judgment from a collection of others, while the axioms are the judgments we are given at the outset. If we think of a deductive system as a formal game, then the rules are the rules of the game, while the axioms are the starting position. And if we think of a deductive system as an algebraic theory, then the rules are the operations of the theory, while the axioms are the generators for some particular free model of that theory.

In set theory, the only rules are the rules of first-order logic (such as the rule allowing us to deduce “A∧B has a proof” from “A has a proof” and “B has a proof”): all the information about the behavior of sets is contained in the axioms. By contrast, in type theory, it is usually the rules which contain all the information, with no axioms being necessary. For instance, in §1.5 we will see that there is a rule allowing us to deduce the judgment “(a, b) : A×B” from “a : A” and “b : B”, whereas in set theory the analogous statement would be (a consequence of) the pairing axiom.

The advantage of formulating type theory using only rules is that rules are “procedural”. In particular, this property is what makes possible (though it does not automatically ensure) the good computational properties of type theory, such as “canonicity”. However, while this style works for traditional type theories, we do not yet understand how to formulate everything we need for homotopy type theory in this way. In particular, in §§2.9 and 2.10 and Chapter 6 we will have to augment the rules of type theory presented in this chapter by introducing additional axioms, notably the univalence axiom. In this chapter, however, we confine ourselves to a traditional rule-based type theory.

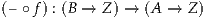

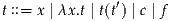

Given types A and B, we can construct the type A → B of functions with domain A and codomain B. We also sometimes refer to functions as maps. Unlike in set theory, functions are not defined as functional relations; rather they are a primitive concept in type theory. We explain the function type by prescribing what we can do with functions, how to construct them and what equalities they induce.

Given a function f : A → B and an element of the domain a : A, we can apply the function to obtain an element of the codomain B, denoted f(a) and called the value of f at a. It is common in type theory to omit the parentheses and denote f(a) simply by fa, and we will sometimes do this as well.

But how can we construct elements of A → B? There are two equivalent ways: either by direct definition or by using λ-abstraction. Introducing a function by definition means that we introduce a function by giving it a name — let’s say, f — and saying we define f : A → B by giving an equation

| (1.2.1) |

where x is a variable and Φ is an expression which may use x. In order for this to be valid, we have to check that Φ : B assuming x : A.

Now we can compute f(a) by replacing the variable x in Φ with a. As an example, consider the function f : N →N which is defined by f(x) :≡ x + x. (We will define N and + in §1.9.) Then f(2) is judgmentally equal to 2 + 2.

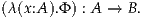

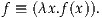

If we don’t want to introduce a name for the function, we can use λ-abstraction. Given an expression Φ of type B which may use x : A, as above, we write λ(x:A).Φ to indicate the same function defined by (1.2.1). Thus, we have

For the example in the previous paragraph, we have the typing judgment

As another example, for any types A and B and any element y : B, we have a constant function (λ(x:A).y) : A → B.

We generally omit the type of the variable x in a λ-abstraction and write λx.Φ, since the typing x : A is inferable from the judgment that the function λx.Φ has type A → B. By convention, the “scope” of the variable binding “λx.” is the entire rest of the expression, unless delimited with parentheses. Thus, for instance, λx.x + x should be parsed as λx.(x + x), not as (λx.x) + x (which would, in this case, be ill-typed anyway).

Another equivalent notation is

We may also sometimes use a blank “–” in the expression Φ in place of a variable, to denote an implicit λ-abstraction. For instance, g(x, –) is another way to write λy.g(x, y).

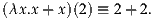

Now a λ-abstraction is a function, so we can apply it to an argument a : A. We then have the following computation rule3 , which is a definitional equality:

where Φ′ is the expression Φ in which all occurrences of x have been replaced by a. Continuing the above example, we have

Note that from any function f : A → B, we can construct a lambda abstraction function λx.f(x). Since this is by definition “the function that applies f to its argument” we consider it to be definitionally equal to f:4

This equality is the uniqueness principle for function types, because it shows that f is uniquely determined by its values.

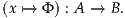

The introduction of functions by definitions with explicit parameters can be reduced to simple definitions by using λ-abstraction: i.e., we can read a definition of f : A → B by

as

When doing calculations involving variables, we have to be careful when replacing a variable with an expression that also involves variables, because we want to preserve the binding structure of expressions. By the binding structure we mean the invisible link generated by binders such as λ, Π and Σ (the latter we are going to meet soon) between the place where the variable is introduced and where it is used. As an example, consider f : N → (N →N) defined as

Now if we have assumed somewhere that y : N, then what is f(y)? It would be wrong to just naively replace x by y everywhere in the expression “λy.x + y” defining f(x), obtaining λy.y + y, because this means that y gets captured. Previously, the substituted y was referring to our assumption, but now it is referring to the argument of the λ-abstraction. Hence, this naive substitution would destroy the binding structure, allowing us to perform calculations which are semantically unsound.

But what is f(y) in this example? Note that bound (or “dummy”) variables such as y in the expression λy.x + y have only a local meaning, and can be consistently replaced by any other variable, preserving the binding structure. Indeed, λy.x + y is declared to be judgmentally equal5 to λz.x + z. It follows that f(y) is judgmentally equal to λz.y + z, and that answers our question. (Instead of z, any variable distinct from y could have been used, yielding an equal result.)

Of course, this should all be familiar to any mathematician: it is the same

phenomenon as the fact that if f(x) :≡∫

12 , then f(t) is not ∫

12

, then f(t) is not ∫

12 but

rather ∫

12

but

rather ∫

12 . A λ-abstraction binds a dummy variable in exactly the same

way that an integral does.

. A λ-abstraction binds a dummy variable in exactly the same

way that an integral does.

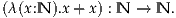

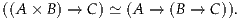

We have seen how to define functions in one variable. One way to define functions in several variables would be to use the cartesian product, which will be introduced later; a function with parameters A and B and results in C would be given the type f : A×B → C. However, there is another choice that avoids using product types, which is called currying (after the mathematician Haskell Curry).

The idea of currying is to represent a function of two inputs a : A and b : B as a function which takes one input a : A and returns another function, which then takes a second input b : B and returns the result. That is, we consider two-variable functions to belong to an iterated function type, f : A → (B → C). We may also write this without the parentheses, as f : A → B → C, with associativity to the right as the default convention. Then given a : A and b : B, we can apply f to a and then apply the result to b, obtaining f(a)(b) : C. To avoid the proliferation of parentheses, we allow ourselves to write f(a)(b) as f(a, b) even though there are no products involved. When omitting parentheses around function arguments entirely, we write fab for (fa)b, with the default associativity now being to the left so that f is applied to its arguments in the correct order.

Our notation for definitions with explicit parameters extends to this situation: we can define a named function f : A → B → C by giving an equation

where Φ : C assuming x : A and y : B. Using λ-abstraction this corresponds to

which may also be written as

We can also implicitly abstract over multiple variables by writing multiple blanks, e.g. g(–, –) means λx.λy.g(x, y). Currying a function of three or more arguments is a straightforward extension of what we have just described.

So far, we have been using the expression “A is a type” informally. We are

going to make this more precise by introducing universes. A universe is a

type whose elements are types. As in naive set theory, we might wish for a

universe of all types  ∞ including itself (that is, with

∞ including itself (that is, with  ∞ :

∞ :  ∞). However, as

in set theory, this is unsound, i.e. we can deduce from it that every type,

including the empty type representing the proposition False (see §1.7), is

inhabited. For instance, using a representation of sets as trees, we can directly

encode Russell’s paradox [Coq92].

∞). However, as

in set theory, this is unsound, i.e. we can deduce from it that every type,

including the empty type representing the proposition False (see §1.7), is

inhabited. For instance, using a representation of sets as trees, we can directly

encode Russell’s paradox [Coq92].

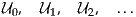

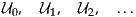

To avoid the paradox we introduce a hierarchy of universes

where every universe  i is an element of the next universe

i is an element of the next universe  i+1. Moreover,

we assume that our universes are cumulative, that is that all the elements of

the ith universe are also elements of the (i + 1)st universe, i.e. if A :

i+1. Moreover,

we assume that our universes are cumulative, that is that all the elements of

the ith universe are also elements of the (i + 1)st universe, i.e. if A :  i then

also A :

i then

also A :  i+1. This is convenient, but has the slightly unpleasant consequence

that elements no longer have unique types, and is a bit tricky in other ways

that need not concern us here; see the Notes.

i+1. This is convenient, but has the slightly unpleasant consequence

that elements no longer have unique types, and is a bit tricky in other ways

that need not concern us here; see the Notes.

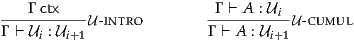

When we say that A is a type, we mean that it inhabits some universe  i.

We usually want to avoid mentioning the level i explicitly, and just assume

that levels can be assigned in a consistent way; thus we may write A :

i.

We usually want to avoid mentioning the level i explicitly, and just assume

that levels can be assigned in a consistent way; thus we may write A :  omitting the level. This way we can even write

omitting the level. This way we can even write  :

:  , which can be

read as

, which can be

read as  i :

i :  i+1, having left the indices implicit. Writing universes in

this style is referred to as typical ambiguity. It is convenient but a

bit dangerous, since it allows us to write valid-looking proofs that

reproduce the paradoxes of self-reference. If there is any doubt about

whether an argument is correct, the way to check it is to try to assign

levels consistently to all universes appearing in it. When some universe

i+1, having left the indices implicit. Writing universes in

this style is referred to as typical ambiguity. It is convenient but a

bit dangerous, since it allows us to write valid-looking proofs that

reproduce the paradoxes of self-reference. If there is any doubt about

whether an argument is correct, the way to check it is to try to assign

levels consistently to all universes appearing in it. When some universe

is assumed, we may refer to types belonging to

is assumed, we may refer to types belonging to  as small types.

as small types.

To model a collection of types varying over a given type A, we use

functions B : A → whose codomain is a universe. These functions are called

families of types (or sometimes dependent types); they correspond to families

of sets as used in set theory.

whose codomain is a universe. These functions are called

families of types (or sometimes dependent types); they correspond to families

of sets as used in set theory.

An example of a type family is the family of finite sets Fin : N → , where

Fin(n) is a type with exactly n elements. (We cannot define the family Fin yet —

indeed, we have not even introduced its domain N yet — but we will be able

to soon; see Exercise 1.9.) We may denote the elements of Fin(n) by

0n, 1n, …, (n- 1)n, with subscripts to emphasize that the elements of Fin(n) are

different from those of Fin(m) if n is different from m, and all are different

from the ordinary natural numbers (which we will introduce in §1.9).

, where

Fin(n) is a type with exactly n elements. (We cannot define the family Fin yet —

indeed, we have not even introduced its domain N yet — but we will be able

to soon; see Exercise 1.9.) We may denote the elements of Fin(n) by

0n, 1n, …, (n- 1)n, with subscripts to emphasize that the elements of Fin(n) are

different from those of Fin(m) if n is different from m, and all are different

from the ordinary natural numbers (which we will introduce in §1.9).

A more trivial (but very important) example of a type family is the

constant type family at a type B :  , which is of course the constant function

(λ(x:A).B) : A →

, which is of course the constant function

(λ(x:A).B) : A → .

.

As a non-example, in our version of type theory there is no type family

“λ(i:N). i”. Indeed, there is no universe large enough to be its codomain.

Moreover, we do not even identify the indices i of the universes

i”. Indeed, there is no universe large enough to be its codomain.

Moreover, we do not even identify the indices i of the universes  i with

the natural numbers N of type theory (the latter to be introduced in

§1.9).

i with

the natural numbers N of type theory (the latter to be introduced in

§1.9).

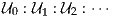

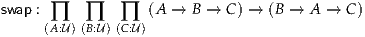

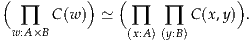

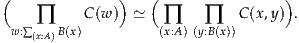

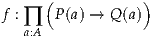

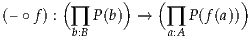

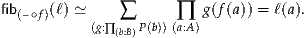

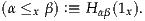

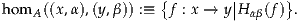

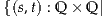

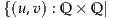

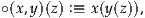

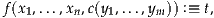

In type theory we often use a more general version of function types, called a Π-type or dependent function type. The elements of a Π-type are functions whose codomain type can vary depending on the element of the domain to which the function is applied, called dependent functions. The name “Π-type” is used because this type can also be regarded as the cartesian product over a given type.

Given a type A :  and a family B : A →

and a family B : A → , we may construct the type of

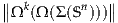

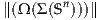

dependent functions ∏(x:A) B(x) :

, we may construct the type of

dependent functions ∏(x:A) B(x) :  . There are many alternative notations for

this type, such as

. There are many alternative notations for

this type, such as

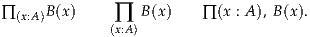

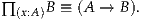

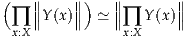

If B is a constant family, then the dependent product type is the ordinary function type:

Indeed, all the constructions of Π-types are generalizations of the corresponding constructions on ordinary function types.

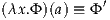

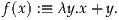

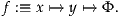

We can introduce dependent functions by explicit definitions: to define f : ∏(x:A) B(x), where f is the name of a dependent function to be defined, we need an expression Φ : B(x) possibly involving the variable x : A, and we write

Alternatively, we can use λ-abstraction

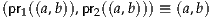

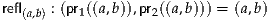

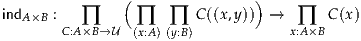

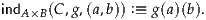

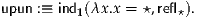

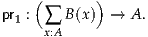

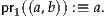

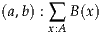

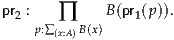

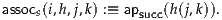

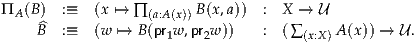

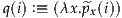

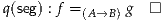

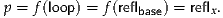

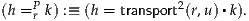

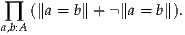

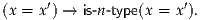

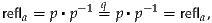

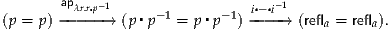

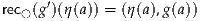

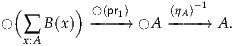

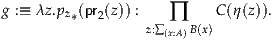

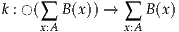

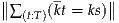

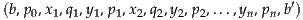

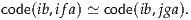

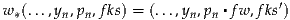

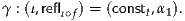

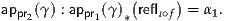

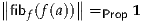

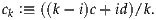

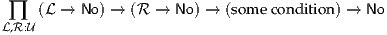

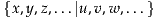

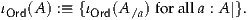

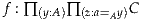

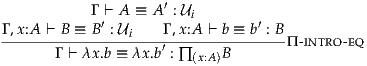

| (1.4.1) |